An unknown situs viscerum inversus totalis, accidentally discovered after computed tomography

- Autores: Montatore M.1, Balbino M.1, Masino F.1, Ruggiero T.2, Guglielmi G.1,2,3

-

Afiliações:

- University of Foggia

- Dimiccoli Hospital

- Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza Hospital

- Edição: Volume 5, Nº 2 (2024)

- Páginas: 370-378

- Seção: Case reports

- ##submission.dateSubmitted##: 01.01.2024

- ##submission.dateAccepted##: 05.03.2024

- ##submission.datePublished##: 20.09.2024

- URL: https://jdigitaldiagnostics.com/DD/article/view/625432

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.17816/DD625432

- ID: 625432

Citar

Resumo

Benign situs inversus totalis of the viscerum is often diagnosed accidentally, rarely in adults, and more frequently in children and neonates, affecting both sexes. In this report, a young female patient accidentally discovered a situs inversus totalis after computed tomography for acute abdominal pain. In this uncommon anatomical abnormality, the major visceral organs are reversed in the opposite direction. This report highlights the importance of being aware of and considering situs inversus in clinical practice, particularly when interpreting imaging findings and planning medical procedures. This is critical for differential diagnosis and comorbidities that may affect those patients.

The cause of situs inversus totalis is still unknown; however, this condition is frequently asymptomatic, particularly in infants, and is sometimes associated with other syndromes. The patient arrived at the emergency department with left flank pain, nausea, and fever. In the first ultrasonography, a strange anatomy was suspected; thus, a contrasted computed tomography was performed. The patient had never had a computed tomography scan before. The identification of situs inversus totalis was unexpected and coincidental; the computed tomography images were carefully examined. In patients with chest or abdominal pain, clinicians may consider situs inversus totalis based on computed tomography, particularly if without clinical and imaging history. This knowledge can help in the differential diagnosis, avoiding unneeded interventions. Moreover, comorbidities that affect several systems, particularly cardiovascular and pulmonary systems, affect quite a few patients with situs inversus totalis, who require careful examination and lifelong monitoring.

Texto integral

INTRODUCTION

Situs viscerum inversus (SI) is a congenital anatomical disorder characterized by a mirror-image reversal of the major visceral organs (complete or incomplete), and the organs are arranged as opposed to the typical arrangement [1–6].

The term “situs” refers to the visceral pattern and individual asymmetric internal organs, which include the gastrointestinal tract, liver, spleen, and lung [7]. SI is classified into solitus (normal), inversus (mirror-image of normal), and situs ambiguous. Thus, situs solitus means normal anatomy, situs inversus describes total reversal, and situs ambiguous denotes any other anomalies of left–right development.

SI could be divided into totalis (SIT) or incomplete; this second condition is also known as “partial,” in which only some visceral organs are transposed, whereas others remain normal. The extent of organ reversal varies; usually, the patient has a normal left-side heart and abdominal organ transposition [8–10]. The origin of these conditions is still unknown; however, they are frequently asymptomatic, particularly in infants. This clinical condition could create several thoracic problems, particularly in the heart level, and abdominal complications [11]. SIT could also complicate the diagnostic assessment and future treatment.

DESCRIPTION OF THE CASE

Medical History

A 56-year-old female patient presented to the emergency department with recurrent and colic left flank pain, particularly on the left side of the abdomen. She experienced intermittent pain migrating upward, to the back, under the shoulder blade and left shoulder [7–12].

She also reported nausea and vomiting, and the first hypothesis of the physician was biliary colic. Thus, some blood test was required, and ultrasonography (US) was initially performed. Due to precarious social conditions, the patient had never had any imaging tests until that moment. The US results were suspicious of something strange in the abdominal anatomy; thus, a contrasted CT was performed (Fig. 1).

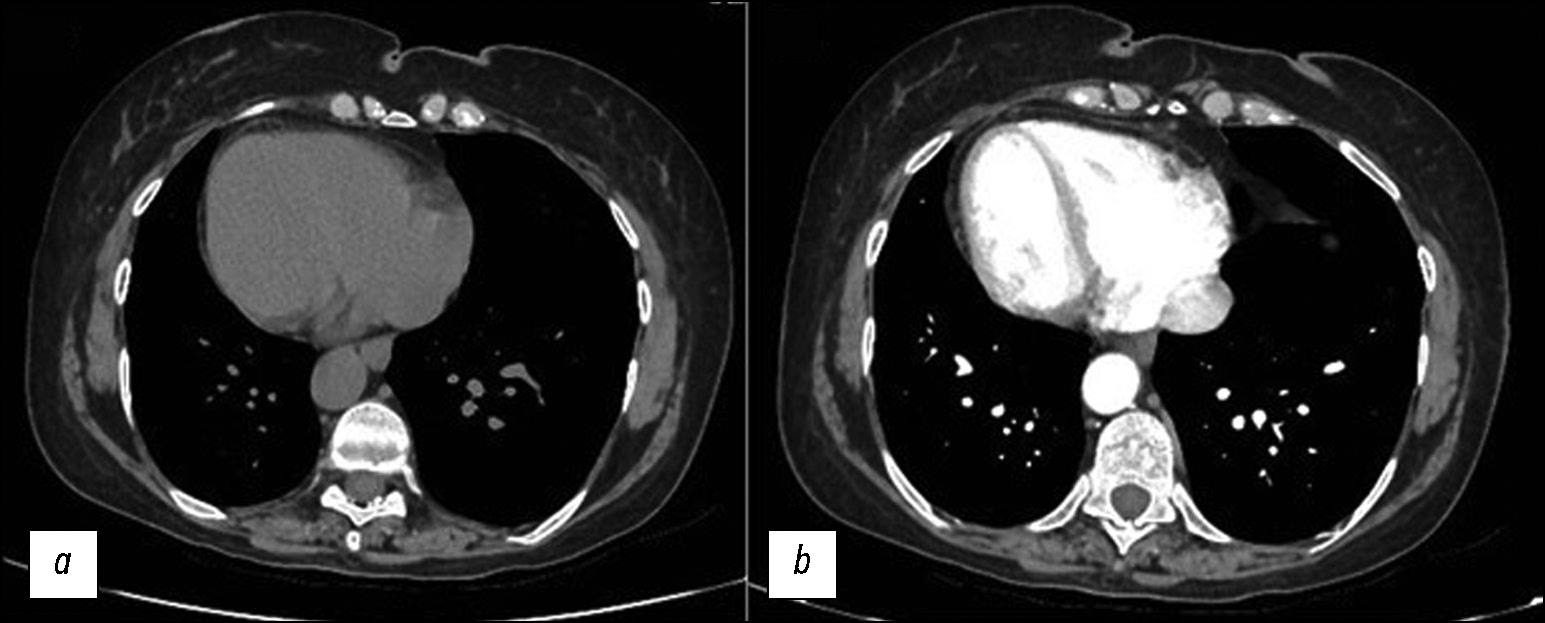

Fig. 1. Axial-computer CT images of the chest without (a) and with contrast medium (b) that show dextrocardia. In this case of situs inversus, the left lung has three lobes, the right lung has two lobes, and the heart apex is on the right.

The patient had not experienced any other significant cardiac or respiratory symptoms or previous CT. The first CT image of the thorax showed dextrocardia and a new diagnostic hypothesis was created. Further imaging studies of the thorax and abdomen confirmed the diagnosis of an unknown SIT (Fig. 2 and 3 ).

Fig. 2. Axial CT images of the abdomen without (a) and with contrast medium (b) show SIT and some calcific calculi in the gallbladder. The stomach and spleen are on the left, and the bigger lobe of the liver is on the right.

Fig. 3. Axial CT image without (a) and with contrast medium (b) that shows the stomach on the right side.

Diagnostic Assessment

The contrasted CT confirmed the SIT: an asymptomatic situs viscerum inversus totalis (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. The SIT is in a coronal plane of the CT (a) and two volume rendering (VR) VR images: (b) from the front and (c) behind.

In addition, the images from the high abdomen show a left-sided gallbladder with some micro-calculi, which could explain the clinical condition of recurrent flank pain on the left [1–7]. For the most part, this unsuspected discovery appeared completely innocuous for the patient’s health [9].

Differential Diagnosis

was a crucial point in this case. The first problem was to know the causes of the acute flank pain on the left [11–13]. The patient has opposing anatomy; thus, the causes of this pain differ from the normal: biliary colic on the left, which is normally localized on the right [9]. This clinical condition was also confirmed by laboratory tests, which revealed a small increase in C-reactive protein level, white blood cell count, and transaminase levels.

Interventions

This case is not directly related to significant symptoms or acute problems due to SIT; instead, the interventions were focused on critical symptoms and the management and prevention of complications [12–16]. Biliary colic treatment aims to reduce pain with painkillers and antispasmodics to relieve symptoms (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. The gallbladder appears with multiple calcific calculi. These CT images without (a) and with (b) contrast medium justify the left-sided abdominal pain.

The future treatment regimen and follow-up for SIT are frequently interdisciplinary, comprising pulmonologists, cardiologists, and gastroenterologists. The management plan is adapted to the needs of each patient.

Follow-up and Outcomes

To optimize care and maintain the best possible quality of life, regular follow-up and communication between physicians and patients are essential in the present and future conditions [15–17].

DISCUSSION

SI refers to a reversal positioning of the heart and major internal organs [1-4]. It is an uncommon congenital anomaly that manifests as a mirror-image transposition of both the abdominal and thoracic organs [5]. Dextrocardia (true mirror-image) is commonly related to SI, and the aorta is up-directed on the opposite side (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. A series of VR images of the mediastinum that show the heart and aorta directed on the right from different perspectives (a in front) (b behind, on the left) (c behind, on the right) on rotation.

This condition could affect the chest, particularly the heart and large blood vessels because each cardiac chamber is asymmetrical; situs also applies to the heart. In addition, the anatomy of the arteries and the abdomen is mirrored (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7. The artery’s anatomy of the abdomen in the case of SIT: on the left, there is the liver, and the spleen is on the opposite side. The first is an angio-map (a) while the second is a VR image (b).

Currently, SIT still has no clear and recognized causes. Given the frequent relationship between aberrant situs and other unusual congenital abnormalities, a study proposed an acquired etiology originating from an in-utero insult that disrupts the normal process of differentiation and orientation [8].

This anatomical condition could complicate the diagnostic process and diagnostic/treatment procedures, particularly invasive ones. Because of their rarity, practicing doctors, such as gastroenterologists, radiologists, and surgeons, typically have little experience with these patients [14–17].

CONCLUSION

Many people with SI are unaware of this condition until they experience some symptoms that require treatment or until they undergo clinical examinations, for example, chest auscultation or US of the abdomen. However, follow-up is required because mirrored architecture can make future disorders more difficult to detect. Thus, regular evaluations and communication between doctors and patients with SIT are critical for optimizing care and preserving the highest possible quality of life, against the resolution of future pathologies and syndromes.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Funding source. This study was not supported by any external sources of funding.

Competing interests. The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contribution. All authors made a substantial contribution to the conception of the work, acquisition, analysis, interpretation of data for the work, drafting and revising the work, final approval of the version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

F. Masino, R. Tupputi — data collection; F. Masino, G. Guglielmi —analysis and interpretation of results; M. Montatore, M. Balbino —draft manuscript preparation, editing the manuscript.

Consent for publication. Written consent was obtained from the patient for publication of relevant medical information and all of accompanying images within the manuscript in Digital Diagnostics Journal.

Sobre autores

Manuela Montatore

University of Foggia

Email: manuela.montatore@unifg.it

ORCID ID: 0009-0002-1526-5047

MD

Itália, FoggiaMarina Balbino

University of Foggia

Email: marinabalbino93@gmail.com

ORCID ID: 0009-0009-2808-5708

MD

Itália, FoggiaFederica Masino

University of Foggia

Email: federicamasino@gmail.com

ORCID ID: 0009-0004-4289-3289

MD

Itália, FoggiaTupputi Ruggiero

Dimiccoli Hospital

Email: rutudott@gmail.com

MD

Itália, BarlettaGiuseppe Guglielmi

University of Foggia; Dimiccoli Hospital; Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza Hospital

Autor responsável pela correspondência

Email: giuseppe.guglielmi@unifg.it

ORCID ID: 0000-0002-4325-8330

MD, Professor

Itália, Foggia; Barletta; FoggiaBibliografia

- Spoon JM. Situs inversus totalis. Neonatal Netw. 2001;20(1):59–63. doi: 10.1891/0730-0832.20.1.63

- Eitler K, Bibok A, Telkes G. Situs Inversus Totalis: A Clinical Review. Int J Gen Med. 2022;15:2437–2449. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S295444

- Tsoucalas G, Thomaidis V, Fiska A. Situs inversus Totalis: Always recall the uncommon. Clin Case Rep. 2019;7(12):2575–2576. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.2433

- Hernanz-Schulman M. Situs inversus? N Engl J Med. 1994;331(3):205. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199407213310317

- Chen XQ, Lin SJ, Wang JJ, et al. “Reverse life”: A rare case report of situs inversus totalis combined with cardiac abnormalities in a young stroke. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2022;28(9):1458–1460. doi: 10.1111/cns.13879

- Chudnoff J, Shapiro H. Two cases of complete stius inversus. Anat. Rec. 2005;74(2):189–194. doi: 10.1002/ar.1090740207

- Baillie M. An Account of a Remarkable Transposition of the Viscera in the Human Body. Lond Med J. 1789;10(Pt 2):178–197.

- Taussig HB. Congenital Malformations of the Heart. New York: Commonwealth Fund; 1948.

- Choe YH, Kim YM, Han BK, Park KG, Lee HJ. MR imaging in the morphologic diagnosis of congenital heart disease. Radiographics. 1997;17(2):403–422. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.17.2.9084081

- Chen W, Guo Z, Qian L, Wang L. Comorbidities in situs inversus totalis: A hospital-based study. Birth Defects Res. 2020;112(5):418–426. doi: 10.1002/bdr2.1652

- Cholst MR. Discrepancies in pain and symptom distribution; position of the testicles as a diagnostic sign in situs inversus totalis. Am. J. Surg. 1947;73(1):104–107. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(47)90297-3

- Mayo CW, Rice RG. A statistical review of seventy-six cases of situs inversus totalis with special reference to biliary disease. Tr. West. 1948;56:188.

- Pipal DK, Pipal VR, Yadav S. Acute Appendicitis in Situs Inversus Totalis: A Case Report. Cureus. 2022;14(3):e22947. doi: 10.7759/cureus.22947

- Mayo CW, Rice RG. Situs inversus totalis: a statistical review of data on 76 cases with special reference to disease of the biliary tract. Arch Surg (1920). 1949;58(5):724–730.

- Borude S, Jadhav S, Shaikh T, Nath S. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy in partial situs inversus. J Surg Case Rep. 2012;2012(5):8. doi: 10.1093/jscr/2012.5.8

- Blegen HM. Surgery in situs inversus. Ann. Surg. 1949;129(2):244–259. doi: 10.1097/00000658-194902000-00009

- Block FB, Michael MA. Acute appendicitis in complete transposition of viscera: report of a case with symptoms referable to right side mechanism of pain in visceral diseases. Ann. Surg. 1938;107(4):511–516. doi: 10.1097/00000658-193804000-00005

Arquivos suplementares