Chronic esophageal fistula as a rare cause of secondary osteomyelitis of the thoracic spine

- Authors: Zarya V.A.1, Gavrilov P.V.1, Makogonova M.E.1, Kozak A.R.1, Vishnevskiy A.A.1

-

Affiliations:

- Saint-Petersburg State Research Institute of Phthisiopulmonology

- Issue: Vol 4, No 3 (2023)

- Pages: 403-410

- Section: Case reports

- Submitted: 16.05.2023

- Accepted: 22.08.2023

- Published: 26.09.2023

- URL: https://jdigitaldiagnostics.com/DD/article/view/430128

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.17816/DD430128

- ID: 430128

Cite item

Abstract

Infectious diseases affecting the spine are inflammatory destructive diseases that involved the organ and its structural elements as a result of infection by hematogenic, lymphogenic, or contact pathways, including may be a complication of surgical intervention. In arriving at an accurate diagnosis, it is extremely important to evaluate the anamnesis, the clinical picture, as well as the data of laboratory studies and radiation diagnostics in the aggregate.

This article presents a clinical case with the development of secondary ThVII–ThVIII vertebral spondylitis due to esophageal fistula. At the initial diagnosis, spondylitis was associated with spinal anesthesia performed six months prior to onset of the disease, as there was a fistulous defect on the skin in the lumbar region. Consequently, surgical interventions were performed three times in a surgical hospital at the place of residence. The data from the endoscopic examination, as well as the patient’s complaints regarding the relationship between meals, the appearance of pain, and the nature of the discharge from the fistula were not taken into account by doctors initially. With the help of an additional examination, including computed tomography of the esophagus with oral contrast and computed tomography fistulography, the main diagnosis was esophageal fistula. Thoracic spondylitis was only a secondary complication.

Thus, the final diagnosis of back pain and fistula in the lumbar region should be formulated after differential diagnosis with alternative diseases of the spine.

Keywords

Full Text

BACKGROUND

Spinal infections are inflammatory destructive disorders of the spine and its structural components (vertebral bodies, intervertebral discs, ligaments, and intervertebral joints). They can be caused by any bacterial agent due to a hematogenous, lymphogenous, or contact infection, or they can be surgical complications (e.g., postoperative and iatrogenic infections) [1].

Spondylitis can be infectious or non-infectious (aseptic). Infectious spondylitis is caused by bacterial, fungal, or parasitic invasions. Spondylitis can cause hematogenous (septic) or contact infections [2–4], as well as postoperative (iatrogenic) complications [5–8]. Some authors reported that spondylitis caused by esophageal perforation can spread posteriorly, resulting in secondary damage to cervical or thoracic vertebrae. For example, Janssen et al. [9] presented cervical and thoracic spondylodiscitis cases caused by esophageal perforation in patients with a history of esophageal cancer who underwent combination therapy. Some of these patients had a recurrence of esophageal fistula after previous nonsurgical and surgical treatment. The authors also reported a female patient who ingested and independently retrieved a toothpick 2 months before the onset of spondylitis, which was accompanied by an epidural and paravertebral abscess. According to Fonga-Djimi et al. [10], an esophageal perforation caused by a foreign body (a toy car wheel) was worsened by mediastinitis and spondylodiscitis. Wadie et al. [11] presented a clinical case of a child with cervical spondylodiscitis and paravertebral soft tissue phlegmon caused by pin ingestion, which resulted in perforation of the posterior pharynx at the level of the laryngeal aperture. Van Ooij et al. [12] described a female patient with cervical spondylitis caused by a fish bone trapped in the esophagus.

When an infection spreads to the chest, it causes empyema, pericarditis, and mediastinitis. As a result of spondylitis, empyema and pericarditis may reoccur. Infections of the anterior thoracolumbar and lumbar spines can result in subdiaphragmatic abscess, peritonitis, and psoas abscess.

Appropriate treatment of infectious spondylitis requires an accurate diagnosis of the etiology and pathogen. The use of X-ray diagnostics is important in the diagnosis of spondylitis. However, X-ray results do not guarantee that the nature and etiology of the infection are accurately identified. Thus, it is necessary to consider the medical history, clinical presentation, laboratory findings, and X-ray findings when diagnosing.

This study presents a rare secondary thoracic spine lesion caused by a chronic esophageal fistula.

CASE REPORT

Patient

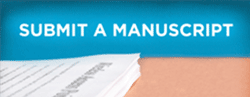

The patient is a 42-year-old female. Back pain and lumbar fistula complaints initially appeared 3 yr ago. According to the medical history, the patient received spinal anesthesia for a cesarean section 6 months prior. The patient experienced fistula relapses approximately three to five times a year. At the presentation, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed bony and fibrous ankylosis ТhVII–ТhVIII (Figure 1), which could indicate both spondylitis in remission and contact spinal infection.

Fig. 1. Thoracic spine MRI: (а) STIR mode, sagittal plane; (b) T1WI mode, sagittal plane; and (c) T1WI mode, coronal plane. The arrows indicate bony and fibrous ankylosis ТhVII–ТhVIII.

At different outpatient facilities, the patient had surgery (fistulotomy and abscessotomy) three times. The surgical specimen contained hemolytic streptococcus susceptible to amoxiclav, ampicillin, cefotaxime, vancomycin, doxycycline, and meropenem. The patient received targeted antibiotic medication with no effect. Before admission to the St. Petersburg Research Institute of Phthisiopulmonology, a computed tomography (CT) revealed symptoms of prior spondylitis ТhVII–ТhVIII and a right-sided psoas abscess (Figure 2).

Fig. 2. Lumbar spine MRI: (a) soft tissue mode, axial plane, and (b) soft tissue mode, coronal plane. The arrows indicate the right psoas muscle abscess.

During the additional history taking, the patient reported an association between his food intake (mostly liquid food), the onset of pain, and the type of discharge from the lumbar fistula tract. Due to these symptoms, a CT esophagography with oral contrast revealed a fistula tract at the ТhVII level extending from the esophagus to the right paravertebral space up to the ThX level and loculated empyema on the right. An additional CT fistulography was performed to determine the length of the fistula tract, with a contract solution (iopromide 370) injected into the lumbar fistula located on the right at the LIII level. The CT fistulography revealed a fistula tract extending from the right psoas major muscle to the ТhVII level. The fistula tract linked with the esophageal lumen at the same level, where the contrast agent was visible (Figure 3).

Fig. 3. (а) CT esophagography with oral contrast, coronal plane and (b and c) CT fistulography, multiplanar reconstruction (MPR), coronal and sagittal plane. The arrows indicate the fistula tract from the esophagus to the right paravertebral space, from the ТhVII to the ThX level.

A follow-up thoracic and lumbar spine MRI performed in the hospital revealed stable changes in the ТhVII–ТhVIII vertebral bodies and bilateral paravertebral abscesses (Figure 4).

Fig. 4. Thoracic and lumbar spine MRI: T2WI mode, coronal plane. Bony and fibrous ankylosis ТhVII–ТhVIII and paravertebral abscesses (arrows) on the left (а), with air bubbles on the right (b).

All laboratory findings were unremarkable, except for the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (30 mm/h). To determine further treatment strategy, an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) was performed, which revealed a fistula tract along the left posterior wall, up to 0.5 cm long, bordered with esophageal epithelium and covered by granulation tissue. The diagnosis of an esophageal fistula in the middle third was confirmed. A post hoc analysis of earlier EGD findings showed that the observed esophageal defect had previously been identified and classified as a diverticulum. However, this information was not taken into consideration in other outpatient facilities.

Thus, a multidisciplinary team made the following diagnosis based on the clinical and X-ray findings: esophagopleural fistula of the lower third of the esophagus. On the right, there is chronic loculated empyema. Chronic contiguous osteomyelitis ТhVII–ТhVIII with a fistula. The patient was sent to the thoracic surgery department for the excision of an esophageal fistula.

DISCUSSION

Spondylitis infections can be caused by various factors, including dental caries, ENT infections, phlegm, and endocarditis. Structural damage to the spine can be caused by hematogenous or contact infections, including penetrating injuries, such as iatrogenic injury. Given the available data, the following questions arise: why was the therapy ineffective, and was the primary cause spondylitis or esophageal fistula?

A history of epidural anesthesia is the main reason supporting infectious spondylitis as the primary process. In such cases, epidural anesthesia is administered at the LIII–LV level. The affected vertebrae in our case are significantly higher. Another factor suggesting spondylitis as the causative cause is a paravertebral abscess on the left (contralateral to the esophageal fistula). Simultaneously, there was no explanation for the severe inflammatory changes in paravertebral tissues. This clinical presentation of spondylitis is not typical. In general, vertebrae are more affected than soft tissues around them. Furthermore, the patient denied any esophageal injury that may lead to a fistula.

Another factor suggesting an esophageal origin of the process was a fistulous contact between the paravertebral abscess and the esophagus (fistula tract diameter up to 5 mm). Endoscopy revealed an esophageal diverticulum and an intact esophageal wall (which was not involved in the inflammatory process); the fistula was bordered by esophageal epithelium. Moreover, the patient associated the pain syndrome with food intake, and the discharge from the lumbar fistula tract resembled previously ingested food or drink.

The long-term disease makes determining the primary process impossible. Considering all available data, esophageal perforation is proposed as the leading cause, followed by spondylitis and paravertebral abscess. Despite the patient denying any esophageal injury, the endoscopic results are most consistent with an esophageal injury caused by an ingested foreign body (such as a fish bone).

CONCLUSION

The cause of the pathological process (esophageal fistula) was unknown, and the patient was treated symptomatically (surgery and antibacterial medication) while in the hospital.

The availability of several modern imaging and surgical procedures does not eliminate the need for a thorough history taking and clinical presentation examination.

Previous diagnoses should be reviewed for compliance with diagnostic criteria in cases when appropriate therapy is ineffective.

Differential diagnosis is critical for systematically assessing possible alternative diagnoses before concluding.

The common logical fallacy of post hoc ergo propter hoc (a false conclusion that confuses co-occurrence with causality) should also be considered.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Funding source. This article was not supported by any external sources of funding.

Competing interests. The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contribution. All authors made a substantial contribution to the conception of the work, acquisition, analysis, interpretation of data for the work, drafting and revising the work, final approval of the version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. V.A. Zarya ― collecting material, writing the article; P.V. Gavrilov ― concept and design of the work, final editing; M.E. Makogonova ― analysis of the data obtained, writing the text; A.R. Kozak ― collecting material, writing the article; A.A. Vishnevskiy ― concept and design of the work, final editing.

Consent for publication. Written consent was obtained from the patient for publication of relevant medical information and all of accompanying images within the manuscript in Digital Diagnostics Journal.

About the authors

Valeriya A. Zarya

Saint-Petersburg State Research Institute of Phthisiopulmonology

Email: zariandra@mail.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0001-7956-3719

Russian Federation, Saint Petersburg

Pavel V. Gavrilov

Saint-Petersburg State Research Institute of Phthisiopulmonology

Author for correspondence.

Email: spbniifrentgen@mail.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0003-3251-4084

SPIN-code: 7824-5374

MD, Cand. Sci. (Med.)

Russian Federation, Saint PetersburgMarina E. Makogonova

Saint-Petersburg State Research Institute of Phthisiopulmonology

Email: MakogonovaME@gmail.com

ORCID iD: 0000-0001-6760-2426

SPIN-code: 6342-8967

MD, Cand. Sci. (Med.)

Russian Federation, Saint PetersburgAndrey R. Kozak

Saint-Petersburg State Research Institute of Phthisiopulmonology

Email: andrkozak@mail.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0002-3192-1430

MD, Cand. Sci. (Med.)

Russian Federation, Saint PetersburgArkadiy A. Vishnevskiy

Saint-Petersburg State Research Institute of Phthisiopulmonology

Email: vichnevsky@mail.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0002-9186-6461

SPIN-code: 4918-1046

MD, Dr. Sci. (Med.)

Russian Federation, Saint PetersburgReferences

- Mushkin AYu, Vishnevsky AA. Clinical recommendations for the diagnosis of infectious spondylitis (draft for discussion). Medical Alliance. 2018;(3):65–74. (In Russ).

- Fowler VG, Justice A, Moore C, et al. Risk factors for hematogenous complications of intravascular catheter-associated Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(5):695–703. doi: 10.1086/427806

- Lu YA, Hsu HH, Kao HK, et al. Infective spondylodiscitis in patients on maintenance hemodialysis: A case series. Ren Fail. 2017;39(1):179–186. doi: 10.1080/0886022X.2016.1256313

- Choi KB, Lee CD, Lee SH. Pyogenic spondylodiscitis after percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2010;48(5):455–460. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2010.48.5.455

- Hsieh MK, Chen LH, Niu CC, et al. Postoperative anterior spondylodiscitis after posterior pedicle screw instrumentation. Spine J. 2011;11(1):24–29. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2010.10.021

- Hanci M, Toprak M, Sarioğlu AC, et al. Oesophageal perforation subsequent to anterior cervical spine screw/plate fixation. Paraplegia. 1995;33(10):606–609. doi: 10.1038/sc.1995.128

- Orlando ER, Caroli E, Ferrante L. Management of the cervical esophagus and hypofarinx perforations complicating anterior cervical spine surgery. Spine. 2003;28:E290–E295. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200308010-00023

- Pompili A, Canitano S, Caroli F, et al. Asymptomatic esophageal perforation caused by late screw migration after anterior cervical plating: Report of a case and review of relevant literature. Spine. 2002;27:E499–E502. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200212010-00016

- Janssen I, Shiban E, Rienmüller A, et al. Treatment considerations for cervical and cervicothoracic spondylodiscitis associated with esophageal fistula due to cancer history or accidental injury: A 9-patient case series. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2019;161(9):1877–1886. doi: 10.1007/s00701-019-03985-3

- Fonga-Djimi H, Leclerc F, Martinot A, et al. Spondylodiscitis and mediastinitis after esophageal perforation owing to a swallowed radiolucent foreign body. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31(5):698–700. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(96)90677-6

- Wadie GM, Konefal SH, Dias MA, McLaughlin MR. Cervical spondylodiscitis from an ingested pin: A case report. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40(3):593–596. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.11.023

- Van Ooij A, Manni JJ, Beuls EA, Walenkamp GH. Cervical spondylodiscitis after removal of a fishbone. A case report. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1999;24(6):574–577. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199903150-00015

Supplementary files