Difficulties in the radiological diagnosis of mature adrenal teratoma mimicking neuroblastoma in a child

- Авторлар: Shchelkanova E.S.1, Tereshchenko G.V.1, Krasnov A.S.1

-

Мекемелер:

- Dmitry Rogachev National Medical Research Center of Pediatric Hematology, Oncology and Immunology

- Шығарылым: Том 5, № 2 (2024)

- Беттер: 379-389

- Бөлім: Case reports

- ##submission.dateSubmitted##: 27.10.2023

- ##submission.dateAccepted##: 13.02.2024

- ##submission.datePublished##: 20.09.2024

- URL: https://jdigitaldiagnostics.com/DD/article/view/622768

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.17816/DD622768

- ID: 622768

Дәйексөз келтіру

Аннотация

The most common adrenal tumor in young children is neuroblastoma, which can be difficult to differentiate from other conditions such as nephroblastoma, adrenal hemorrhage, angiomyolipoma, myelolipoma, and adenoma. This article describes a case of teratoma, one of the rarest adrenal tumors in children. Initially, despite its large size, it demonstrated all the radiological and histological signs of neuroblastoma. Teratomas are germ cell tumors usually found in the gonads. Adrenal teratomas are extremely rare, accounting for approximately 0.13% of all adrenal tumors. Typically, adrenal teratomas are asymptomatic, as the retroperitoneal space is large enough to accommodate the growth of the tumor without causing symptoms. For the first time in domestic literature, we present a clinical case of adrenal teratoma in a 3-month-old child. The article also presents a detailed description of the diagnostic process and challenges that radiologists and clinicians face when encountering a common tumor in a very rare location for children. This report aimed to help physicians increase awareness of this rare condition and include adrenal teratomas in the potential differential diagnosis of adrenal neoplasms.

Негізгі сөздер

Толық мәтін

INTRODUCTION

Primary adrenal tumors are a critical area of clinical oncology that presents diagnostic and therapeutic challenges.

Based on the fourth edition of Classification of Tumors of Endocrine Organs by the World Health Organization published in 2017, all adrenal tumors can be classified into two large groups [1]:

1) Tumors of the adrenal cortex;

2) Tumors of the adrenal medulla and extra-adrenal paraganglia.

The first group comprises tumors that originate from the adrenal cortex or predominantly affect it, including adenocarcinoma, adenoma, sex cord stromal tumors, adenomatoid tumors, mesenchymal and stromal tumors (myelolipoma and schwannoma), and hematolymphoid tumors.

The second group encompasses pheochromocytoma, paraganglioma, and neuroblastic adrenal tumors (neuroblastoma, ganglioneuroblastoma, and ganglioneuroma).

Currently, neuroblastoma is the most prevalent adrenal tumor in children and incorporates such differential diagnosis categories as nephroblastoma, adrenal hemorrhage, angiomyolipoma, myelolipoma, and adenoma [2–4].

This article details a case report of primary mature teratoma of the left adrenal gland in a child. The tumor was initially diagnosed as neuroblastoma. The article also provides differential diagnosis categories for this condition.

As per the literature review, approximately 20 comparable cases in children have been reported worldwide [3, 5, 6]. However, we were unable to locate relevant case reports in Russian literature.

DESCRIPTION OF THE CASE

Medical History

The patient has been unwell since August 2020 (age of 2 months), when a routine abdominal ultrasound (US) revealed a left kidney space-occupying mass (197 cm3). The patient’s previous medical history was unremarkable.

According to the medical history:

On September 21, 2020, the patient was admitted to the Urology Department. The tumor markers assessed as of September 22, 2020 were:

- Neuron-specific enolase (NSE) elevated to 24.7 ng/mL (normal range: 0–16.3 ng/mL);

- Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) elevated to 971 ng/mL (normal range: 323 ± 278 ng/mL).

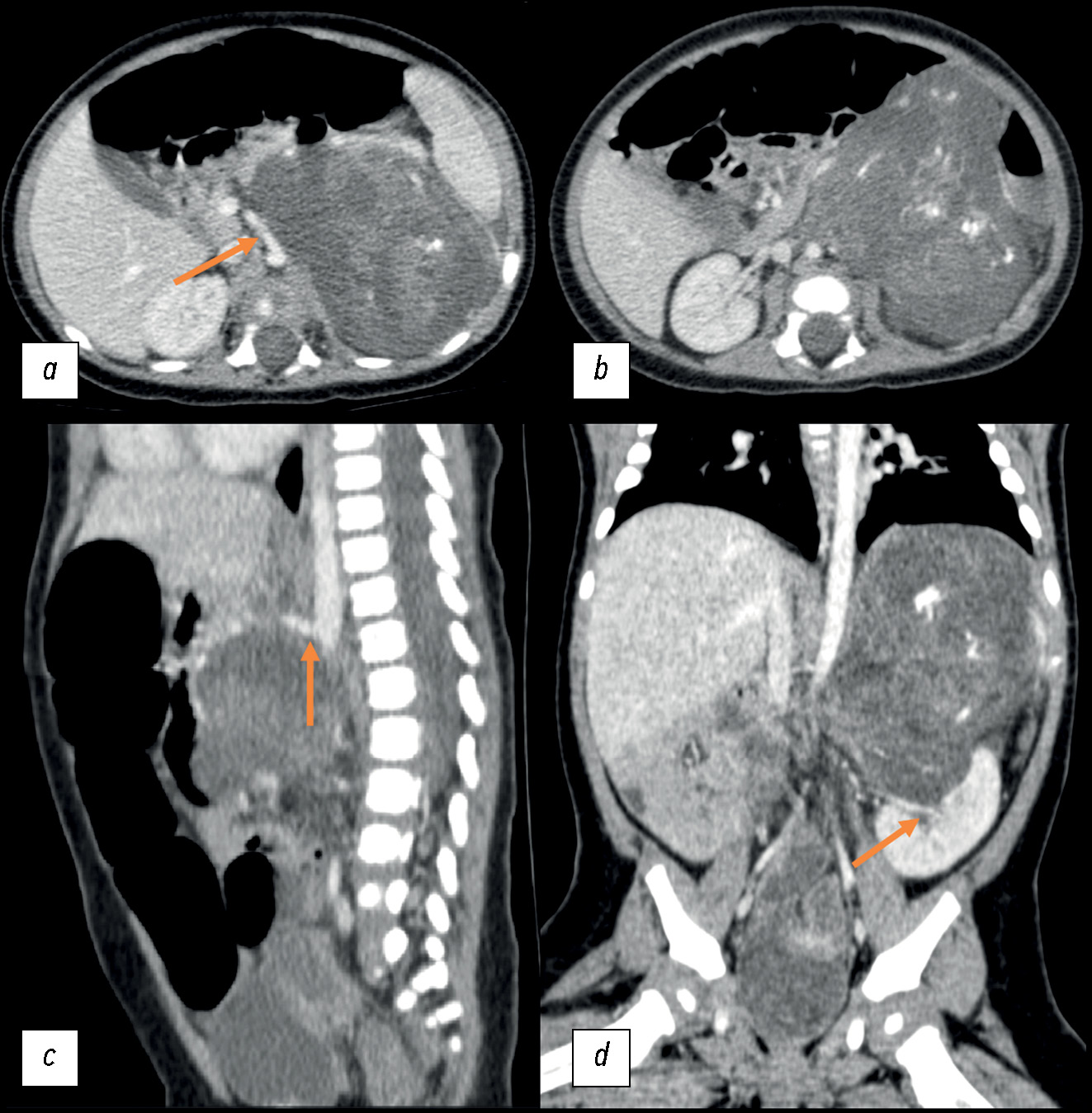

September 23, 2020: A contrast-enhanced abdominal multislice computed tomography (MSCT) revealed a retroperitoneal space-occupying mass on the left, measuring 81 × 71 × 87 mm (volume: 260 cm3), with a heterogeneous structure incorporating areas of calcification and inclusion cysts; the contrast uptake was weak. The neoplasm extended to the renal sinus area, without discernible signs of extension into the renal parenchyma. The adrenal gland extended across the lateral contour. The renal vessels on the left side followed the tumor contour; the superior mesenteric artery was displaced to the right, while the celiac artery was displaced upward (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Initial abdominal computed tomography using intravenous contrast dated September 23, 2020, a pattern of a space-occupying retroperitoneal mass on the left: (a) axial plane; the arrow indicates the displacement of the superior mesenteric artery to the right; (b) axial plane; (c) sagittal plane; the arrow indicates the upward displacement of the celiac artery; (d) coronal plane; the arrow indicates the tumor extension into the renal sinus.

September 29, 2020: No tumor cells were detected in myelogram findings.

The surgery, which involved laparotomy and retroperitoneal tumor biopsy, was conducted in early October. The histological examination revealed the tumor to be a high-grade neuroblastoma. The diagnosis was further corroborated by the examination of histologic specimens at the Dmitry Rogachev National Medical Research Center of Pediatric Hematology, Oncology, and Immunology. A cytogenetic test was not performed because of insufficient sample size.

Following the examination, a clinical diagnosis of left-sided retroperitoneal neuroblastoma extending to the abdominal cavity was established. Therapy was initiated in accordance with the NB-2004 protocol.

October 16, 2020: The patient was referred for follow-up magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at their place of residence. The MRI revealed disease progression, with a tumor size increase to 104 × 77 × 118 mm (volume: 491 cm3). The tumor exhibited a cystic and solid structure, with areas of hemorrhage and signs of active contrast uptake. The adrenal gland was spread along the lateral contour of the tumor. The tumor contour was followed by the renal vessels on the left; the superior mesenteric artery was displaced to the right, and the celiac artery was displaced upward. The study did not incorporate contrast sequences or weighted sequences with fat suppression (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging dated November 16, 2020: (a) Т1-weighted image, sagittal plane; (b) Т2-weighted image, sagittal plane; (c, d) Т1-weighted images, axial plane; a space-occupying mass of the left adrenal gland, with an increase in the size over time. Orange arrows indicate an attenuated signal from the cystic tumor component; the blue arrow indicates an enhanced signal from the solid tumor component.

Hospitalization

Because of the disease progression, the patient was admitted to the Clinical Oncology Department of the Dmitry Rogachev National Medical Research Center for further examination and determining the suitable treatment strategy.

Upon admission, the test for NSE was repeated, revealing elevated levels of 19.64 ng/mL (normal range: 0–16.3 ng/mL). A blood test for cortisol was conducted to exclude a hormone-producing tumor, yielding a value of 17.3 µg/dL (normal range: 3.7–19.4 µg/dL).

October 30, 2020: A metaiodobenzylguanidine scintigraphy demonstrated no reliable signs of radiopharmaceutical uptake (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Metaiodobenzylguanidine scintigraphy dated October 30, 2020. There was no indication of radiopharmaceutical uptake.

November 1, 2020: A contrast-enhanced MRI was conducted as a follow-up to ascertain the type of the tumor. A series of abdominal scans revealed persistent signs of a cystic and solid retroperitoneal mass lesion on the left, which was irregularly shaped had relatively clear and smooth contours with areas of intratumor hemorrhage (restricted diffusion areas in diffusion-weighted images) and fat deposits (signal dropout in the spectral pre-saturation with inversion recovery (SPIR) mode). The total dimensions of the lesion were up to 89 × 112 × 141 mm (volume: 731 cm3). The tumor volume increased by 49% in comparison to the previous investigation. A focal MRI contrast absorption in solid components was observed because of intravenous contrast enhancement. The tumor caused caudal displacement of the left kidney to the small pelvic area. The left adrenal gland was not visualized. The spleen was displaced forward, and the tumor margin was clearly visible. The celiac artery followed the medial contour, while the spleen vessels followed the anterior tumor contour. The pancreas extended across the anterior tumor contour and was in close proximity to the tumor. The caudal misplacement of the left hemidiaphragm was a result of the tumor’s upper margin being contiguous to it, which in turn reduced the volume of the left lung (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Contrast-enhanced abdominal magnetic resonance imaging dated November 11, 2020, coronal (a) and axial (b–e) planes: (a) Т2-weighted image; diminished volume of the left lung caused by the tumor pressing on the left hemidiaphragm (double orange arrow), displacement of the left kidney to the pelvic area (orange arrow); (b) Т2-weighted image; multiple cysts in the tumor (orange arrow); (c) Т1-weighted image +С; focal contrast uptake in solid components (orange arrow); (d) T2 SPIR; signal dropout because of fat deposits in the tumor (orange circle); (e) diffusion-weighted image; restricted diffusion areas due to intratumor hemorrhages (orange arrows).

The MRI revealed fat deposits (signal dropout in the SPIR mode) that are atypical for neuroblastoma. Hence, for the first time, a germ cell tumor, i.e., retroperitoneal teratoma (possibly, left adrenal gland teratoma) or a mesenchymal tumor, was suspected.

The following day, abdominal computed tomography was conducted, which verified calcification and fat deposits in the mass with the cystic and solid components, with a weak contrast uptake (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography dated November 1, 2020: (a, b) axial plane; (c) sagittal plane; (d) coronal plane. Orange arrows indicate the hypodense areas (fat deposits) of the tumor, with a density of –80 HU; blue arrows indicate calcification.

Considering an increase in the tumor size during the initial chemotherapy course, tumor characteristics with signs of fat deposits and tumor infiltration of the renal sinus area, as well as the absence of cytogenetic test findings, surgery was recommended. This procedure included repeated laparotomy and retroperitoneal tumor resection to conduct routine histopathological examination and cytogenetic testing.

November 4, 2020: Laparotomy, retroperitoneal tumor resection, and left ureter stenting were performed as part of surgical treatment.

November 9, 2020: The laboratory findings revealed that the AFP levels returned to normal (51 ng/mL).

Histopathological findings: the morphological pattern was consistent with mature teratoma of the left adrenal gland. The tumor originated from the adrenal medulla.

Thus, the final diagnosis of ature teratoma of the left adrenal gland was established.

The patient was discharged in stable condition at the age of 5 months to be dynamically observed by a pediatric oncologist at their place of residence. There were no indications to continue any particular therapy.

DISCUSSION

Teratomas are germ cell tumors that develop from totipotent cells [5]. They comprise well-differentiated or not fully differentiated elements of at least two germ cell layers (endoderm, ectoderm, and/or mesoderm).

It is hypothesized that the initial involvement of the retroperitoneal space is a consequence of the disruption of normal embryological migration of primary germ cells at various points between their development in the yolk sack and their “final destination” in the labioscrotal swellings [7]. There are four histological variants of teratomas: mature, immature, with malignant transformation, and monodermal [7]. Mature teratomas are well-differentiated relative to germ cell layers. Immature teratomas are not completely differentiated and are comparable to fetal or embryonic tissue [8]. Teratomas may contain hair, skin, teeth, nerves, adipose tissue, cartilages, etc. [3]. Adrenal teratomas are exceedingly uncommon, and teratomas that originate outside the gonads are exceedingly unusual. The Peking Union Medical College in China conducted the most extensive study of adrenal disorders, treating 3,901 patients between March 2009 and February 2014. Of these, five patients (four adults and one child) were diagnosed with primary adrenal teratoma, accounting for 0.13% [9].

Adrenal teratoma patients typically do not exhibit any clinical symptoms of the disease since the retroperitoneal space is sufficiently vast to accommodate unrestricted tumor growth. Certain patients complain of lower back pain, a palpable mass in the abdomen, and upper abdominal pain [3].

In children, abdominal ultrasound is typically the preferred imaging method, The detection rate of masses in the early phases has been enhanced by the combination of prophylactic abdominal and retroperitoneal ultrasound one month after birth and antenatal ultrasound examination of the fetus [10]. Ultrasound enables the identification of cystic, solid, and other complex tumor components [11].

MSCT and MRI are essential for evaluating the size of tumors in the retroperitoneal space and their association with large vessels. This enhances preoperative planning and increases the possibility of total tumor resection with a lower risk of iatrogenic injury [12]. Fat deposits, cysts, and calcification are considered significant predictors of a benign teratoma on MSCT [13]. MRI exhibits a high natural contrast of soft tissues; moreover, it is overly sensitive to small fat deposits when sequences with fat suppression are employed. Retroperitoneal teratomas can express AFP; thus, its serum levels are a reliable parameter for the diagnosis and evaluation of tumor recurrence [14].

This case report underscores the need to thoroughly examine the tumor node structure and assess the density of different tumor components. The retrospective examination of the diagnostic errors revealed that teratoma could have been suspected as early as the initial abdominal MSCT, as the presence of small hypodense inclusions (–70 HU) consistent with the lipid component of the tumor and uncharacteristic of neuroblastoma should have been considered (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Initial contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography dated September 23, 2020, axial plane. Arrows indicate small hypodense areas of the tumor, with a density of −70 HU.

Moreover, the diagnosis of adrenal teratoma was inferred from the clear and smooth contours of the tumor, which displaced vessels without surrounding them; in contrast, neuroblastoma exhibits indistinct, irregular contours and affects vessels by infiltrating them. The presence of a cystic and solid component and calcification is typical for both tumors. The absence of radiopharmaceutical uptake during scintigraphy, low NSE levels, and high AFP levels are also suggestive of teratoma. The histopathological examination’s errors may be attributed to a biopsy performed at a less informative site and a limited sample size.

Notably, adrenal tumors, except for neuroblastomas, are exceedingly uncommon in children. Teratomas should be differentiated from other tumors that contain a fat component and calcification.

Fat-containing adrenal tumors include myelolipoma, lipoma, and myelosarcoma; microscopic fat inclusions can be found in adenoma, pheochromocytoma, and adrenocortical carcinoma.

Myelolipoma is typically detected at the age of 50–70 years, more commonly in the right adrenal gland [15]. Large adipose deposits are depicted on MSCT, with cloudy or mottled tissue areas that have a higher density of 20–30 HU (myeloid elements). In rare cases, small, calcified inclusion may be observed.

Adrenal lipoma is an extremely rare condition that primarily impacts the right adrenal gland, with a median diagnosis age of 54 years. Unlike teratoma, it is a hypodense mass that exclusively contains a fat component [16].

Despite the rarity of liposarcoma in children, it should not be disregarded during the differential diagnosis. It is characterized by indistinct, irregular contours and invasion into the surrounding tissues and vessels. Metastases are frequently observed [17].

The most prevalent adrenal neoplasms with calcified components are metastatic lesions (in our case, this was a primary tumor, and no other neoplasms were identified) and tuberculosis involvement (in the present case, the patient was not exposed to infectious diseases, and there were no signs of tuberculosis) [3].

CONCLUSION

Primary adrenal teratoma is extremely rare; however, it exhibits distinct radiographic signs that, in certain cases, may be remarkably comparable to those of other common pediatric tumors at this site. In our case, the radiologist could have suspected this disease as early as at the initial phases of the diagnostic search. Misdiagnosis was the consequence of a lack of awareness regarding an uncommon tumor site, inaccurate interpretation of histopathological examination findings, and a lack of attention to detail during the assessment of the tumor node structure. To enhance the quality of diagnostic radiology, it is imperative to discuss rare clinical cases and analyze the mistakes.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Funding source. This article was not supported by any external sources of funding.

Competing interests. The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contribution. All authors made a substantial contribution to the conception of the work, acquisition, analysis, interpretation of data for the work, drafting and revising the work, final approval of the version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. E.S. Shchelkanova — review of publications on the topic of the article, writing the text of the article, preparation of a list of references; G.V. Tereshchenko — approval of the final version of the publication; A.S. Krasnov — editing the text of the manuscript.

Consent for publication. Written consent was obtained from the patient’s legal representatives for publication of relevant medical information and all of accompanying images within the manuscript in Digital Diagnostics Journal.

Авторлар туралы

Ekaterina Shchelkanova

Dmitry Rogachev National Medical Research Center of Pediatric Hematology, Oncology and Immunology

Хат алмасуға жауапты Автор.

Email: dr.shelkanova@yandex.ru

ORCID iD: 0009-0002-3582-8783

SPIN-код: 9198-4674

Ресей, Moscow

Galina Tereshchenko

Dmitry Rogachev National Medical Research Center of Pediatric Hematology, Oncology and Immunology

Email: Galina.Tereshenko@fccho-moscow.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0001-7317-7104

SPIN-код: 9413-2500

MD, Cand. Sci. (Medicine)

Ресей, MoscowAlexey Krasnov

Dmitry Rogachev National Medical Research Center of Pediatric Hematology, Oncology and Immunology

Email: Alexey.Krasnov@fccho-moscow.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0003-1099-9332

SPIN-код: 3238-4124

Ресей, Moscow

Әдебиет тізімі

- WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. WHO classification of tumours of endocrine organs, 4th ed. Lloyd R.V., Osamura RY, Kloppel G, Rosai J, editors. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2017.

- Emre Ş, Özcan R, Bakır AC, Kuruğoğlu S, et al. Adrenal masses in children: Imaging, surgical treatment and outcome. Asian J Surg. 2020;43(4):207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.asjsur.2019.03.012

- He C, Yang Y, Yang Y, et al. Teratoma of the adrenal gland: clinical experience and literature review. Gland Surg. 2020;9(4):1056–1064. doi: 10.21037/gs-20-648

- Feoktistova EV, Uskova NG, Varfolomeeva SP, et al. Differential diagnosis of congenital cystic neuroblastoma and prenatal adrenal hemorrhage in children of the first months of life. Pediatric Hematology/Oncology and Immunopathology. 2017;16(1):62–68. doi: 10.24287/1726-1708-2017-16-1-62-68

- Wang X, Li X, Cai H, et al. Rare Primary Adrenal Tumor: A Case Report of Teratomas and Literatures Review. Front Oncol. 2022;12:830003. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.830003

- AlQattan A, Alsharit M, Alsaihaty E, et al. The ‘’Monstrous tumor’’ of Adrenal gland: A case report and review of literature on adrenal teratomas. Int. J. Surg. Open. 2023;60:100696. doi: 10.1016/j.ijso.2023.100696

- Craig WD, Fanburg-Smith JC, Henry LR, et al. Fat-containing lesions of the retroperitoneum: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2009;29(1):261–290. doi: 10.1148/rg.291085203

- Wetherell D, Weerakoon M, Williams D, et al. Mature and Immature Teratoma: A Review of Pathological Characteristics and Treatment Options. Med Surg Urol. 2014;3(1):124. doi: 10.4172/2168-9857.1000124

- Li S, Li H, Ji Z, Yan W, Zhang Y. Primary adrenal teratoma: Clinical characteristics and retroperitoneal laparoscopic resection in five adults. Oncol Lett. 2015;10(5):2865–2870. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.3701

- Sandoval JA, Williams RF. Neonatal Germ Cell Tumors. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2015;11(3):205–215. doi: 10.2174/1573396311666150714105531

- Wootton-Gorges SL, Thomas KB, Harned RK, et al. Giant cystic abdominal masses in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2005;35(12):1277–1288. doi: 10.1007/s00247-005-1559-7

- Zhao Z, Deng X, Peng L, Kong X. Case Report Management of retroperitoneal teratoma in infants younger than one-year-old. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2018;11(2):1362–1366.

- Singh AP, Jangid M, Morya DP, Gupta A. Retroperitoneal Teratoma in an Infant. Journal of Case Reports. 2014;4(2):317–319. doi: 10.17659/01.2014.0079

- Rattan KN, Kadian YS, Nair VJ, et al. Primary retroperitoneal teratomas in children: a single institution experience. Afr J Paediatr Surg. 2010;7(1):5–8. doi: 10.4103/0189-6725.59350

- Lam AK. Lipomatous tumours in adrenal gland: WHO updates and clinical implications. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2017;24(3):65–79. doi: 10.1530/ERC-16-0564

- Tejedor DC, Gutierrez VR, Afonso JM, et al. Adrenal lipoma: A case report and literature review. Urol Case Rep. 2020;34:101506. doi: 10.1016/j.eucr.2020.101506

- Liao T, Du W, Li X, et al. Recurrent metastatic retroperitoneal dedifferentiated liposarcoma: a case report and literature review. BMC Urol. 2023;23(1):63. doi: 10.1186/s12894-023-01252-3

Қосымша файлдар