Difficulty in the differential diagnosis of peritoneal carcinomatosis and tuberculosis in a young female patient with ascites: a case report

- Авторлар: Nefedova T.S.1, Shumskaya Y.F.2, Yurazh M.V.1, Panferov A.S.1, Senchikhin P.V.1,3, Grabarnik A.E.4, Shchekoturov I.O.1, Mnatsakanyan M.G.1

-

Мекемелер:

- The First Sechenov Moscow State Medical University

- Research and Practical Clinical Center for Diagnostics and Telemedicine Technologies

- National Medical Research Center for Phthisiopulmonology and Infectious Diseases

- Moscow Scientific and Clinical Center for Tuberculosis Control

- Шығарылым: Том 4, № 4 (2023)

- Беттер: 643-652

- Бөлім: Case reports

- ##submission.dateSubmitted##: 08.08.2023

- ##submission.dateAccepted##: 07.11.2023

- ##submission.datePublished##: 15.12.2023

- URL: https://jdigitaldiagnostics.com/DD/article/view/568134

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.17816/DD568134

- ID: 568134

Дәйексөз келтіру

Аннотация

The differential diagnosis between peritoneal tuberculosis and peritoneal carcinomatosis is quite challenging because of the similarity of the clinical picture and laboratory and instrumental examination data. Peritoneal tuberculosis and peritoneal carcinomatosis may present with the development of ascites, lymph nodes, and intestinal loop conglomerates. This article presents the clinical case of a young patient who, after her second childbirth, noted the appearance of intense pain in the neck and between the scapulae. Two months later, she experienced pneumonia with a positive reaction to antibiotic therapy. After another 2 months, she experienced recurrent ascites and gastrointestinal symptoms for the first time. The examination revealed ovarian masses and signs of peritoneal carcinomatosis and lung nodules. However, the clinical presentation was atypical for peritoneal carcinomatosis, and lung lesions were suspicious for tuberculosis, which allowed us to hypothesize the presence of tuberculosis of multiple localizations. The diagnosis was confirmed by laparoscopy with a biopsy of the involved tissues and subsequent histological and laboratory confirmation of the etiological role of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The described case demonstrates the importance of using all available diagnostic methods to establish the causes of ascites in young female patients for differential diagnosis between specific and neoplastic etiologies.

Толық мәтін

BACKGROUND

Abdominal tuberculosis (TB) affects the liver, spleen, large and small intestines, intra-abdominal lymph nodes, pelvic organs, and peritoneum [1]. Peritoneal TB may manifest as ascites, conglomeration of lymph nodes and intestinal loops, and high levels of cancer antigen (CA)-125, which requires differential diagnosis with peritoneal carcinomatosis because of the progression of ovarian cancer, particularly in routine clinical practice [2, 3]. The situation is further complicated by the lack of a noninvasive “gold standard” for diagnosing tuberculous peritonitis [4].

Herein, the case of a 21-year-old woman with multifocal TB, with recurrent ascites as a leading clinical manifestation, was presented. The case description was prepared in accordance with the CAse REports guidelines [5].

CASE REPORT

In January 2021, a 21-year-old female patient (born and living in Dagestan) presented to a gastroenterologist with the following complaints:

- Abdominal enlargement

- Hypogastric pain predominantly on the right side radiating to the right lower extremity

- Diarrhea occurring up to 3 times per day without abnormal admixtures

- Decreased appetite

- Exertional dyspnea

- General weakness

Case History

In February 2020, 2 days after the second delivery, the patient experienced pain in her left neck, shoulder, and scapula, including at night. However, she did not seek medical attention.

In April 2020, the patient experienced pain in the right chest and right hypochondrium with a fever up to 39°C. A local outpatient chest X-ray imaging revealed right-sided multifocal pneumonia complicated by pleurisy. Antibacterial therapy (meropenem and azithromycin) was initiated with a positive clinical effect. Because of the positive clinical response, lung changes were interpreted by the local healthcare professionals as community-acquired nonspecific bacterial pneumonia.

Since June 2020, the patient noticed an increase in abdominal volume with decreased appetite. Abdominal ultrasonography showed a moderate amount of free fluid. Spironolactone 50 mg/day was ineffective, and the abdominal volume continued to increase.

In September 2020, an abdominal tap was performed at a local inpatient hospital. Approximately 500 mL of light fluid was obtained; however, it was not tested.

In December 2020, ascites had increased again. Blood tests showed a high C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 28.4 (reference, <5) mg/L and a high erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 48 (reference, <20) mm/h, with leukopenia of up to 3 (reference, 4–9) mln/μL. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest and abdomen revealed bilateral multifocal pulmonary inflammation, hepatosplenomegaly, ascites, a conglomerate of large- and small-bowel loops in the left abdomen, and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy. Pelvic ultrasonography showed an enlarged left ovary with cystic transformation and a large amount of pelvic fluid. A puncture of the rectouterine pouch yielded 1100 mL of straw-colored fluid. Cytology revealed focal accumulations of neutrophils, rare lymphocytes, and mesotheliocytes on a structureless substance background. No microflora growth was observed in the culture. Treatment included amoxicillin + clavulanic acid 875/125 mg twice daily and spironolactone 100 mg/day. After the initiation of therapy, the patient had diarrhea up to 5–7 times per day. A stool test for Clostridium difficile toxins A and B was negative.

In January 2021, the patient consulted a gastroenterologist with the abovementioned complaints and was admitted to the Gastroenterology Department of the Sechenov University Clinical Hospital.

Physical, Laboratory, and Instrumental Data

CRP and ESR remained unchanged in the presence of leukopenia. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed no abnormalities. Colonoscopy revealed intact mucosa. Biopsies showed no microscopic changes in the colon or ileum.

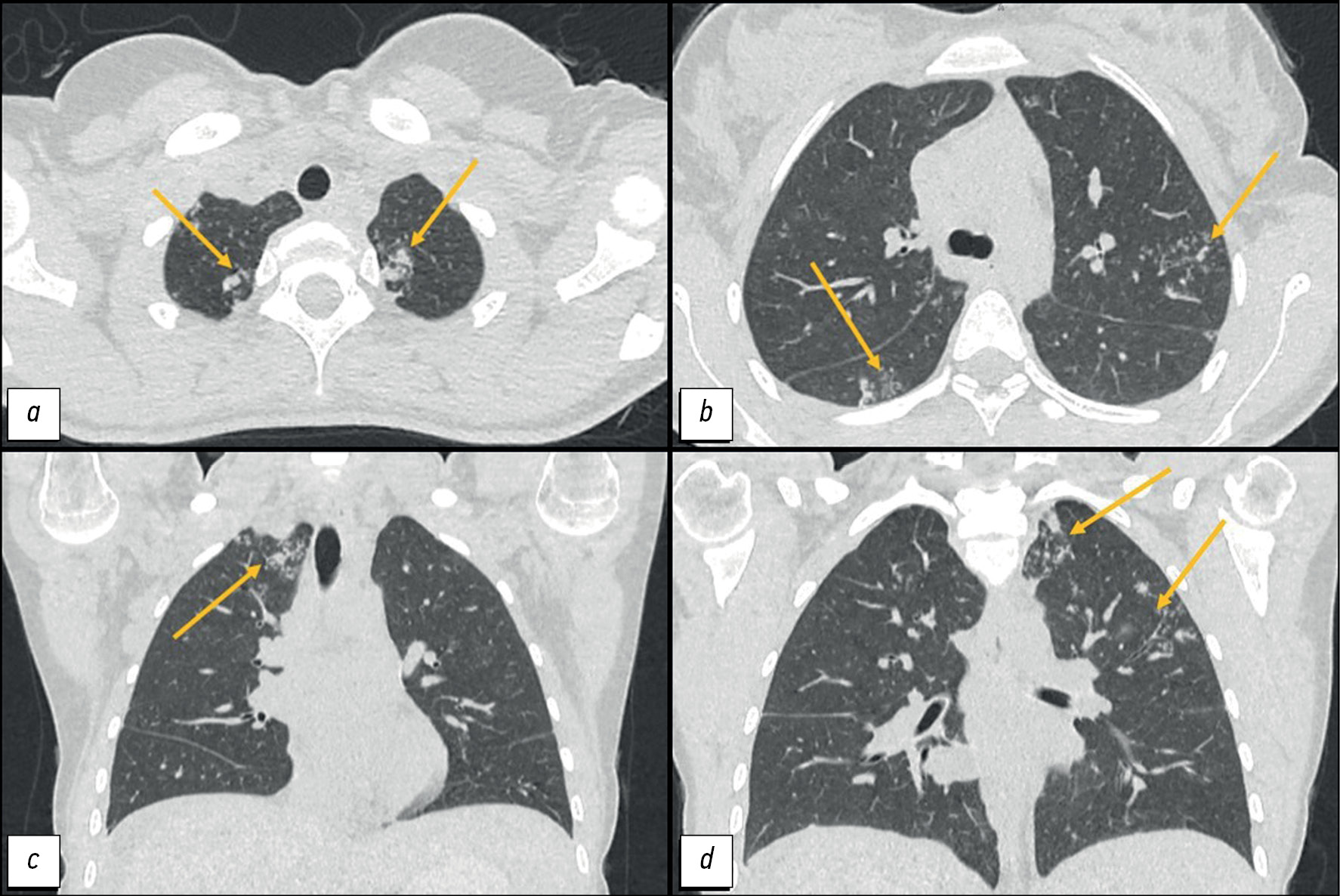

CT of the lungs showed the following:

- In segments I, II, and VI: “tree-and-bud” structures and peribronchial lesions up to 8 mm in size with a tendency to merge.

- In the apex of the left lung: an irregularly shaped subpleural consolidation zone of 15 × 11 mm,

- Mediastinal lymphadenopathy of up to 12 mm (Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Computed tomography of the chest organs: a, d - axial plane; b, c — coronal plane. Arrows indicate peribronchial foci and zones of consolidation in the apices of the lungs.

Pelvic ultrasonography findings were as follows:

- The contours of both ovaries were uneven because of small echogenic round masses with relatively clear and uniform contours (up to 3 mm diameter, no blood flow reported).

- Free pelvic fluid

- In the presence of free fluid bilaterally adjacent to the ovaries: echogenic elongated structures with a clear and relatively uniform contour, approximately 56 mm long and 15 mm thick, with visible changes in blood flow.

An abdominal CT with intravenous contrast was performed because of changes seen on previous examinations:

- A large amount of free liquid

- The mesentery and greater omentum were compressed and edematous, and lymph nodes up to 8 mm were visualized.

- The ovaries were not enlarged. They had an uneven contour and a heterogeneous structure (Figure 2).

Fig. 2. Computed tomography of the abdominal and pelvic organs with contrast enhancement: a - coronal plane; b, c — axial plane. The arrows indicate: a, b — ovaries with a heterogeneous structure and uneven contours; c — infiltration and swelling of the greater omentum.

The patient also had a consultation with a gynecologist. The serum CA-125 level was 268 (reference, <35) IU/mL However, the angiotensin-converting enzyme activity and levels of carcinoembryonic antigen, β-subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin, and tumor marker HE4 were within the reference ranges.

Given the history of conglomerate small and large bowel loops and intestinal symptoms, magnetic resonance (MR) enterography was performed, which showed circular homogeneous thickening of the wall and narrowing of the lumen of the first parts of the small intestine to 12 mm over approximately 50 cm with increased contrast enhancement. A “pie-shaped” infiltration of the greater omentum and a large amount of free fluid in the abdominal cavity was observed (Figure 3).

Fig. 3. Magnetic resonance imaging, T2-weighted images: a, b - axial plane; c — coronal plane; orange arrow—thickened wall of the jejunum; yellow arrow - compacted and thickened greater omentum.

A TB specialist suggested that the patient had peritonitis and a pulmonary inflammatory process. Repeat abdominal puncture revealed a clear fluid with a predominance of lymphocytes, 58 g/L of protein, 200 mmol/L of glucose, and a serum ascitic albumin gradient of 9.6 g/L. Acid-fast mycobacteria were not detected. However, polymerase chain reaction revealed the DNA of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MBT).

The patient was further evaluated at a specialized clinic. Positive T-SPOT.TB and ascitic fluid test results were obtained. Diagnostic laparoscopy revealed disseminated lesions of the parietal and visceral peritoneum and infiltrative lesions of the fallopian tubes. Ziehl–Neelsen staining of biopsy specimens from the peritoneum and fallopian tubes did not reveal acid-fast mycobacteria or MBT complex DNA. On histological examination, all the materials consisted of fragments of granulation tissue with many macrophage–epithelioid giant–cell granulomas, some with areas of caseous necrosis.

Diagnosis

Based on the examination data, the patient was diagnosed with “multifocal tuberculosis: disseminated pulmonary tuberculosis in the infiltration phase, MBT (−); tuberculosis of the intrathoracic lymph nodes in the infiltration phase; peritoneal tuberculosis, active phase, MBT(−), MBT DNA(+); tuberculous salpingo-oophoritis, active phase, MBT (−); tuberculosis of the intra-abdominal lymph nodes in the infiltration phase. Ascites.”

Treatment

Based on clinical guidelines, the treatment was as follows:

- Meropenem 1.0 g three times daily IV

- Isoniazid 10% 5.0 mL IV

- Moxifloxacin 0.4 g IV

- Rifampicin 0.45 g PO

- Pyrazinamide 1.5 g

The above treatment was supplemented with hepatoprotective and detoxifying therapy.

Follow-up and Outcomes

During treatment, positive changes were noted: the pain syndrome was relieved, and the ascites was completely resolved. The patient was discharged for follow-up by a local TB specialist. Six months later, with specific therapy, the patient’s condition was satisfactory, stable normothermia was reported, she had no pain, and ascites did not recur.

DISCUSSION

Diagnosis of peritoneal TB is difficult because of the nonspecific presentation and lack of relevant diagnostic markers. A primary peritoneal TB is extremely rare. Therefore, signs of specific lesions in the most common sites, particularly the lungs, should be excluded. Peritoneal contamination is possible from primary lesions in the intestine or fallopian tubes, and in this case, the lung tissue would be intact [6].

In this case, whether the primary lesion was the lung or the small intestine, which was involved according to MR enterography, was unclear.

The present TB course is characterized by a tendency to generalize and an increased incidence of exudative forms. As in our case, high CA-125 levels make the differential diagnosis of cancer difficult. I.H. Chen et al. reported that the CA-125 level increase in TB is 3–5 times lower than that in malignant ovarian tumors [7]. However, other authors reported an increase in CA-125 of up to 18,554 U/mL [8].

Peritoneal TB is characterized by recurrent ascites, although adhesive and caseous necrosis is possible. The examination of the ascitic fluid revealed pleocytosis caused by lymphocytosis and a high protein concentration with a serum ascitic albumin gradient of <11 g/L, which was also reported in our case. Many foreign studies have confirmed the high diagnostic value of determining adenosine deaminase in ascitic fluid [9]; however, this technique is not widely used at present. Among laboratory methods, interferon-gamma release assays (IGRAs) have the greatest diagnostic value for peritoneal TB, with a sensitivity of 91.18%, specificity of 83.33%, and accuracy of 90% [10]. Initially, IGRAs were specifically designed to replace tuberculin tests in the diagnosis of latent TB and were not intended for diagnosing active TB, which can only be determined by microbiological tests. However, EL-Deeb et al. showed a high specificity of this method in diagnosing the active form of TB and advantages in diagnosing the latent form in high-risk groups; however, this issue requires further research [10]. In our case, the results of the T-SPOT.TB tests of both blood and ascitic fluid were positive while the TB process was active.

Radiological methods play an important role in the differential diagnosis of TB and peritoneal carcinomatosis. RV Ramanan and V. Venu described the CT sign of “omental cake” (radiologically detected diffuse infiltration of the omentum). According to the authors, it helps in differentiating between these conditions [11]. However, other authors have pointed out the insufficient diagnostic value of radiological methods in such a clinical setting. For example, J. Kattan et al. reported that when CT and MRI suggested peritoneal carcinomatosis, laparoscopy and biopsy confirmed the TB origin of the lesion [12]. In abdominal TB, wall thickening predominated in the terminal ileum and cecum [13]. In our case, MR enterography of the abdomen showed a homogeneous, actively contrast-enhancing, stenotic thickening of the proximal small intestine, infiltration of the omentum, and small peritoneal lesions, suggesting miliary dissemination (see Figure 1).

The “gold standard” for diagnosing peritoneal TB is laparoscopy, followed by the histological examination of intraoperative biopsy specimens. The diagnosis was confirmed by the visualization of the miliary lesion and detection of specific granulomas with caseous necrosis [14]. Note that B. Huang et al. reported the lack of advantages of laparoscopy as an independent diagnostic method over a combination of laboratory tests (CA-125, T-SPOT.TB, and ESR) [15].

CONCLUSION

The differential diagnosis between TB and peritoneal carcinomatosis requires the use of all available techniques because of the similarity of the clinical manifestations of the diseases. Peritoneal TB should be considered one of the possible etiologic causes of ascites, including in women with peritoneal abnormalities and high CA-125 levels, even when the clinical picture suggests a malignant ovarian tumor with carcinomatosis.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Funding source. This article was prepared by a group of authors as a part of the research and development effort titled “Opportunistic screening of high-profile and other common diseases,” No. 123031400009-1, (USIS No. 123031400009-1) in accordance with the Order No. 1196 dated December 21, 2022 “On approval of state assignments funded by means of allocations from the budget of the city of Moscow to the state budgetary (autonomous) institutions subordinate to the Moscow Health Care Department, for 2023 and the planned period of 2024 and 2025” issued by the Moscow Health Care Department.

Competing interests. The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contribution. All authors made a substantial contribution to the conception of the work, acquisition, analysis, interpretation of data for the work, drafting and revising the work, final approval of the version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. The major contributions are distributed as follows: T.S. Nefedova, Yu.F. Shumskaya — concept, collection and processing of data, data analysis, manuscript writing; P.V. Senchikhin, M.V. Yurazh — collection and processing of data, manuscript writing; A.S. Panferov — concept, manuscript editing; I.O. Shchekoturov —manuscript editing, preparation of illustrative material; A.E. Grabarnik, M.G. Mnatsakanyan — final editing, manuscript approval.

Consent for publication. Written consent was obtained from the patient for publication of relevant medical information and all of accompanying images within the manuscript in Digital Diagnostics Journal.

Авторлар туралы

Tamara Nefedova

The First Sechenov Moscow State Medical University

Email: prosto.toma.22@gmail.com

ORCID iD: 0000-0002-6718-8701

SPIN-код: 3097-4977

Ресей, Moscow

Yuliya Shumskaya

Research and Practical Clinical Center for Diagnostics and Telemedicine Technologies

Хат алмасуға жауапты Автор.

Email: yu.shumskaia@npcmr.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0002-8521-4045

SPIN-код: 3164-5518

Ресей, Moscow

Marta Yurazh

The First Sechenov Moscow State Medical University

Email: yurazh_m_v@staff.sechenov.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0001-6759-6820

SPIN-код: 4872-7130

Ресей, Moscow

Alexandr Panferov

The First Sechenov Moscow State Medical University

Email: panferov_a_s@staff.sechenov.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0002-4324-7615

SPIN-код: 5747-9842

MD, Cand. Sci. (Med.), Assistant Professor

Ресей, MoscowPavel Senchikhin

The First Sechenov Moscow State Medical University; National Medical Research Center for Phthisiopulmonology and Infectious Diseases

Email: paulus200271@mail.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0003-0496-4504

SPIN-код: 8293-6144

MD, Cand. Sci. (Med.)

Ресей, Moscow; MoscowAlexei Grabarnik

Moscow Scientific and Clinical Center for Tuberculosis Control

Email: a.grabarnik@mail.ru

ORCID iD: 0009-0009-4885-3321

SPIN-код: 5923-8630

MD, Cand. Sci. (Med.)

Ресей, MoscowIgor Shchekoturov

The First Sechenov Moscow State Medical University

Email: samaramail@bk.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0002-2167-8908

SPIN-код: 6885-6834

MD, Cand. Sci. (Med.)

Ресей, MoscowMarina Mnatsakanyan

The First Sechenov Moscow State Medical University

Email: mnatsakanyan08@mail.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0001-9337-7453

SPIN-код: 2015-1822

MD, Dr. Sci. (Med.), Professor

Ресей, MoscowӘдебиет тізімі

- Hopewell PC, Jasmer RM. Overview of clinical tuberculosis. In: Tuberculosis and the tubercle bacillus. 2004:13–31. doi: 10.1128/9781555817657.ch2

- Oge T, Ozalp SS, Yalcin OT, et al. Peritoneal tuberculosis mimicking ovarian cancer. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 2012;162(1):105–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2012.02.010

- Nissim O, Ervin FR, Dorman SE, Jandhyala D. A Case of Peritoneal Tuberculosis Mimicking Ovarian Cancer in a Young Female. Case Reports in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2022;2022. doi: 10.1155/2022/4687139

- Zhou XX, Liu Y-L, Zhai K, Shi H-Z, Tonga Z-H. Body fluid interferon-γ release assay for diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific Reports. 2015;5(1):15284. doi: 10.1038/srep15284

- Barber MS, Aronson JK, von Schoen-Angerer T, et al. CARE guidelines for case reports: explanation and elaboration document. Translation into Russian. Digital Diagnostics. 2022;3(1):16–42. doi: 10.17816/DD105291

- Gudu W. Isolated ovarian tuberculosis in an Immuno-competent woman in the post partum period: case report. Journal of Ovarian Research. 2018;11:1–4. doi: 10.1186/s13048-018-0472-2

- Chen IH, Torng P-L, Lee C-Y, et al. Diagnosis of peritoneal tuberculosis from primary peritoneal cancer. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(19):10407. doi: 10.3390/ijerph181910407

- Maheshwari A, Gupta S, Rai S, et al. Clinical and laboratory characteristics of patients with peritoneal tuberculosis mimicking advanced ovarian cancer. South Asian Journal of Cancer. 2021;10(2):102–106. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1736030

- Zhou R, Qiu X, Ying J, et al. Diagnostic performance of adenosine deaminase for abdominal tuberculosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Public Health. 2022;10:938544. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.938544

- EL-Deeb M, Malwany HEL, Khalil Y, Mourad S, et al. Interferon Gamma Release Assays (IGRA) in the Diagnosis of Active Pulmonary Tuberculosis. Journal of High Institute of Public Health. 2014;44(1):33–40. doi: 10.21608/JHIPH.2014.20355

- Ramanan RV, Venu V. Differentiation of peritoneal tuberculosis from peritoneal carcinomatosis by the Omental Rim sign. A new sign on contrast enhanced multidetector computed tomography. European Journal of Radiology. 2019;113:124–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2019.02.019

- Kattan J, Haddad FGh, Menassa-Moussa L, et al. Peritoneal tuberculosis: A forsaken yet misleading diagnosis. Case Reports in Oncological Medicine. 2019;2019. doi: 10.1155/2019/5357049

- Debi U, Ravisankar V, Prasad KK, et al. Abdominal tuberculosis of the gastrointestinal tract: revisited. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2014;20(40):14831. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i40.14831

- Purbadi S, Indarti J, Winarto H, et al. Peritoneal tuberculosis mimicking advanced ovarian cancer case report: Laparoscopy as diagnostic modality. International Journal of Surgery Case Reports. 2021;88:106495. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2021.106495

- Huang B, Cui DJ, Ren Y, et al. Comparison between laparoscopy and laboratory tests for the diagnosis of tuberculous peritonitis. Turkish journal of medical sciences. 2018;48(4):711–715. doi: 10.3906/sag-1512-147

Қосымша файлдар