目前对分化型甲状腺癌患者放射性碘治疗准备工作主要方面的看法:文献综述

- 作者: Reinberg M.V.1, Slashchuk K.Y.1, Trukhin A.A.1, Avramova K.I.1, Sheremeta M.S.1

-

隶属关系:

- Endocrinology Research Centre

- 期: 卷 4, 编号 4 (2023)

- 页面: 543-568

- 栏目: 科学评论

- ##submission.dateSubmitted##: 08.07.2023

- ##submission.dateAccepted##: 05.09.2023

- ##submission.datePublished##: 15.12.2023

- URL: https://jdigitaldiagnostics.com/DD/article/view/532728

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.17816/DD532728

- ID: 532728

如何引用文章

详细

甲状腺癌是内分泌系统中最常见的肿瘤。它占所有恶性肿瘤的1%-3%(截至2021年)。在90%的病例中,可发现分化型甲状腺癌(乳头状癌和滤泡状癌)。它们的预后相对较好。

对于高分化甲状腺癌患者来说,手术治疗和随后的激素抑制治疗、放射性碘治疗相结合的预后良好。不过,放射性碘治疗仍有可能出现反应不充分的情况。这可能与许多因素有关,包括准备阶段。迄今为止,如何选择最佳的放射性碘治疗准备方法仍是一个重要问题。

该出版物对有关高分化甲状腺癌患者接受放射性碘治疗的准备问题的科学文献进行了综述。根据主要专家团体的建议和有关该主题的出版物,我们对患者准备工作的原则进行了介绍和总结。文章还考虑了(1)与放射性碘治疗相关的不良反应;(2)患者的生活质量;(3)疗效;(4)治疗的长期结果。

这篇综述的主要目的是提供一个全面的视角,介绍为高分化甲状腺癌患者接受放射性碘治疗做准备的方法,强调现有的问题和有前途的研究方向,以便使治疗现代化,实现个性化治疗。

在National Library of Medicine、The Cochrane Library和Google Scholar数据库中检索了截至2023年1月底发表的科学文章和综述。检索时使用了以下关键词:为放射性碘治疗做准备、促甲状腺素α、停用甲状腺激素、副作用、禁碘饮食、涎腺炎、原发性甲状腺功能减退症、生活质量、甲状腺切除术、分化型甲状腺癌、放射性碘治疗的疗效。采用了以下科学界关于高分化甲状腺癌的建议:俄罗斯高分化甲状腺癌临床指南、美国甲状腺协会、欧洲甲状腺协会、American Thyroid Association、European Thyroid Association、The National Comprehensive Cancer Network、European Association of Nuclear Medicine、British Thyroid Association、European Society for Medical Oncology。排除标准为:未提供全文的文章;非英语或俄语文章;类似主题的系统综述。共选择并分析了124个资料来源。本文强调现代放射性碘治疗患者准备工作的总体趋势和当前存在的问题,指出在治疗个性化框架内优化放射性碘治疗准备的概念,最后得出结论。

全文:

绪论

甲状腺癌有五种组织学类型:

- 乳头状(80%–85%);

- 滤泡状(10%–15%);

- 髓样型(5%);

- 低分化型(1%);

- 未分化型(0.1%–2%)。

前两种类型属于高分化癌症,预后相对较好。在全世界恶性肿瘤发病率结构中,首次发现的恶性肿瘤占所有病例的1%至3%。

在甲状腺结节性肿瘤中,癌症的发病率高达 5%(有数据显示高达20%)[1],年均增长率为3%。自2011年以来,发病率增长了36%,死亡率一直保持在较低水平[2]。这主要归功于诊断方法的改进,包括超声检查的广泛实用性和质量的提高。

尽管对手术和放射性碘治疗反应良好,但仍有20%的患者可能会发现疾病复发,8%的病例预后不良[1]。2021年,俄罗斯甲状腺癌死亡率为每10万人996例。在2011年至2021年期间,15岁以下儿童恶性甲状腺癌的“粗略”发病率(40%)有显著的统计学增长[2]。

高分化甲状腺癌患者,包括复发风险较高的患者,总体生存状况一般较好:对放射性碘治疗的反应率约为90%-95%[3]。有远处转移、放射性碘治疗第一疗程后反应不完全以及疾病扩散的患者预后较差:根据不同的资料来源[3,4],这类患者的10年和5年总生存率分别约为30%和55%,肿瘤特异性生存率约为30%-65%[5]。根据A.Hassan等人的研究[6],中危患者的5年无复发生存率为52%,高危患者为17%。目前,关于放射性碘治疗不完全反应和甲状腺癌进展的原因还没有统一的共识,这可能是由许多因素复杂的相互作用造成的,包括患者准备放射性碘治疗的方法和原则。寻找治疗反应不完全的原因,开发提高生活质量的方法和治疗方法仍然是一个紧迫的问题。

放射性碘治疗指的是对高分化甲状腺癌的根治性治疗,是主要针对疾病复发风险为中度和高度的患者(根据科学界的标准[7-11])的综合疗法的一部分。放射性核素治疗的目的是甲状腺切除术后残留的甲状腺组织消融,并能够积聚 碘-131(I-131)的肿瘤组织和转移灶清除。

放射性碘治疗的疗效取决于多种因素的综合作用,包括肿瘤组织学类型、原发肿瘤和/或转移灶的大小、是否存在局部和/或远处转移灶、诊断时患者的年龄、检测到高分化甲状腺癌时的甲状腺激素状态、进行放射性碘治疗的方法等。一个重要的标准是符合放射性碘治疗的准备条件,以优化残留组织甲状腺细胞或 甲状腺癌细胞对I-131的摄取。一般认为,体内充足的甲状腺激素水平和低碘含量是肿瘤细胞充分捕获放射性药物的必要条件。

这些条件可通过停用甲状腺激素或注射重组人促甲状腺激素α来实现,并在放射性碘治疗之前坚持限碘饮食。然而,关于这些建议的时间安排和严格遵守程度对长期治疗效果的影响,目前还没有达成共识。在世界范围内(表1),以下步骤是公认的放射性碘治疗准备标准:

- 提前 3-6 周取消左甲状腺素钠,或:

- 用左甲状腺素替代左甲状腺素钠2周,然后再取消2周;

- 对疾病复发/进展风险较低和中危组的患者使用重组人促甲状腺激素;

- 限碘饮食1–4周(当单次和/或每日尿液中的碘浓度<50–100μg/L)。

表1。不同科学界对放射碘治疗的要求和方法的特点比较

建议 | 准备方法 | 限碘饮食 | 重组人促甲状腺激素 | 放射性碘治疗前的 甲状腺激素 | 碘浓度 |

俄罗斯临床建议[7] | 提前4周取消左甲状腺素钠 或 重组人促甲状腺激素(2次注射) | 2周 | 不详 | >30mIU/L | 不详 |

European Association of Nuclear Medicine[8] | 左甲状腺素钠在3–4周内取消 或 左甲状腺素钠/左甲状腺素/重组人促甲状腺激素(2次注射) | 1–2周 | 低危/中危患者,或有远处转移的患者的标签外治疗 | >30mIU/L | 适量:<100μg/L最佳:<50μg/L |

American Thyroid Association[9] | 左甲状腺素钠在3–4周内取消 或 左甲状腺素钠/左甲状腺素/重组人促甲状腺激素(2次注射) | 1–2周 | 低危/中危患者 | >30mIU/L | 适量:<100μg/L最佳:<50μg/L |

European Thyroid Association[10] | 左甲状腺素钠在3–4周内取消 或 左甲状腺素钠/左甲状腺素/重组人促甲状腺激素(2次注射), 最好是重组人促甲状腺激素 | 可开具饮食处方,但其益处尚未得到确证。建议停用含碘药物。 | 不推荐用于远处转移患者 | >30mIU/L | 适量:<100μg/L最佳:<50μg/L |

European Society for Medical Oncology[11] | 左甲状腺素钠在4–5周内取消 或 重组人促甲状腺激素(2次注射) | 不详 | 不详 | >30mIU/L | 不详 |

British Thyroid Association[12] | 左甲状腺素钠在4周内取消 或 左甲状腺素钠/左甲状腺素/重组人促甲状腺激素(2次注射) | 1–2周 | 不推荐用于远处转移患者、肿瘤大量扩散到甲状腺囊外的患者 | >30mIU/L | 不详 |

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network[13] | 左甲状腺素钠在4–6周内取消 或 重组人促甲状腺激素(2次注射) | 10–14天 | 未被批准用于远处转移患者 | >30mIU/L | <100μg/L |

鉴于目前的趋势,有必要分别考虑每个放射性碘治疗准备点对患者生活质量、副作用发生和放射性碘治疗疗效的影响。

停用甲状腺激素

首先采用了为期6周的左甲状腺素钠停药方案作为放射性碘治疗的准备方法,但这一方案导致了严重的甲状腺功能减退,并产生了相关副作用。随后,为了在不影响放射性碘治疗疗效的前提下提高生活质量,人们采用了不同的方案。因此,A.Golger等人和T.Davids等人总结说,对大多数患者来说,停用左甲状腺素钠三周就足够了[14,15]。另外,也可以采用一种办法,即用左甲状腺素代替左甲状腺素钠两周,然后在同一时期取消左甲状腺素。然而,根据一些研究,这种方法并不会给患者的生活质量带来额外的好处[16,17],有时还会加重左甲状腺素的副作 用[18]。在俄罗斯市场上,三碘甲状腺原氨酸制剂的供应有限,加上上述因素,可能会使这种方法对患者不太方便。

尽管提出了这些方法,但停用左甲状腺素钠四周或停用左甲状腺素两周就导致临床意义上的甲状腺功能减退,并伴随着相关的副作用,大大降低了患者的生活质量。此外,接受抑制治疗的患者对甲状腺功能减退症状的耐受性也会降低。研究表明了,大多数患者在停止抑制性治疗两周后,影响生活质量的甲状腺功能减退症状就会开始加重[19]。在使用问卷对数据进行分析时,也观察到在停用左甲状腺素钠两周后生活质量有所下降[20]。

关于将左甲状腺素钠的停药时间缩短至2–3周的讨论非常激烈,这样可能会同样有效地达到目标甲状腺激素水平和长期治疗效果。

在Y.Liel等人对一组13名患者进行的研究中,所有患者在停用左甲状腺素钠平均17天后,甲状腺激素浓度大于30mIU/L,并观察到甲状腺激素呈指数型增长[21]。

R.Luna等人在对一组34名患者的甲状腺激素水平进行研究时发现了,停用左甲状腺素钠后的第7天、第14天、第21天和第28天,平均甲状腺激素水平分别为20、46、75和112mIU/L,这与促甲状腺激素的线性增长特征相符。因此,75%的患者在2周后甲状腺激素达到30mIU/L以上,100%的患者在停药3周后甲状腺激素浓度达到30mIU/L以上[19]。

A.Piccardo 等人的研究表明了,在2周(85名 患者)和4周(137名患者)取消左甲状腺素钠的组别中,对 放射性碘治疗的反应并无差异:在3–4年的随访期内,反应率为82%。此外,放射性碘治疗前的 甲状腺激素水平对不完全治疗反应没有影响[22]。其他作者也得出了类似的结 论[23,24]。

作为一种替代方法,P.W.Rosário等人提出了一种方案,即在放射性碘治疗前6-8周将左甲状腺素钠剂量降至0.8mg/(kg×天),这与在停药背景下发生的甲状腺功能减退水平测量有关,而且还可以避免使用昂贵的重组人促甲状腺激素。因此,在24名接受传统方案治疗的患者中,有71%的人报告健康状况恶化,而在27名接受减量方案治疗的患者中,只有23%的人出现甲状腺功能减退症状。第二组患者的实验室指标也更好。采用传统方案的病例中有63%发现肌酐升高,而采用减量方案的病例中仅有30%,60%的患者注意到了不同准备方法的差异,如果再次需要刺激甲状腺激素,100%的患者会选择减量方案。减量方案组和传统方案组的放射性碘治疗有效率分别为75%和79%[25]。

由于研究受限于患者样本较少和之前的放射性碘治疗,该方案在其他国家的临床医生中并未得到广泛宣传。不过,在为低危和中危患者准备诊断程序和 放射性碘治疗时,可以考虑使用这种方法,这还需要进一步研究。

优化患者的放射性碘治疗准备是一个实际的研究方向。从上述研究中可以看出,在不影响放射性碘治疗疗效的情况下,左甲状腺素钠的停药时间可以缩短至2–3周。这可能会降低临床上明显的甲状腺功能减退的风险,并改善患者的生活质量,因为大多数患者的甲状腺功能减退症状在停用左甲状腺素钠两周后开始加重。

甲状腺激素浓度大于30MIU/L是不是过时的教条?

关于对残留甲状腺组织进行放射性碘治疗前甲状腺激素的最佳浓度还存在争议。据推测,肿瘤和残留甲状腺组织摄取I-131放射性药物的效率取决于钠碘同向转运体的表达水平,而钠碘同向转运体的表达水平又取决于甲状腺激素的浓 度[26,27]。D.Yu.Semenov等人的研究[28]表明了,高分化甲状腺癌细胞膜上钠碘同向转运体表达的平均值不超过4.5%,最大值达到10%,而正常甲状腺癌组织的表达水平为30%-50%。超过60%的复发高分化甲状腺癌患者的钠碘同向转运体表达水平低于1%。根据理论,钠碘同向转运体的低表达可能是复发风险和疾病严重程度的独立预后因素,但这一课题还需要进一步研究。

1977年,C.J.Edmonds等人首次得出了结论,甲状腺激素小于30mIU/L时,肿瘤不可能充分摄取I-131,此后,这一临界点一直被用作病人为放射性碘治疗做好充分准备的指标,也是大多数后续研究的基准。需要注意的是,该研究中并非所有患者都能在“目标”甲状腺激素值下摄取足够的I-131,样本量较小,且纳入了有甲状腺癌远处转移的患者,这些患者对放射性药物摄取的影响可能比甲状腺激素浓度更大。最后,研究数据没有经过统计分析,因此我们无法得出明确的最终结论[26]。

在2021年发表的一项最新研究中,J.Xiao等人报告说,与接受放射性碘治疗时甲状腺激素浓度等于或小于30mIU/L的一组患者相比,甲状腺激素浓度为30–70mIU/L的一组患者显示出更好的治疗效果。此外,甲状腺激素大于70mIU/L组与甲状腺激素浓度为30–70mIU/L组的放射性碘治疗有效率并无差异[29]。不过,需要注意的是,统计分析中排除了疾病复发风险高的患者;他们占甲状腺激素小于30mIU/L组患者的大多数,而且由于甲状腺癌的分期,他们对治疗的反应可能明显更差。因此,根据甲状腺激素值,我们无法在统计学上可靠地说明放射性碘治疗的效果较差。另一个有趣的发现是,在停用左甲状腺素钠的第4周末,76%的患者甲状腺激素水平达到了约70mIU/L,其中46%的患者甲状腺激素浓度大于100mIU/L。作者总结说,由于甲状腺激素浓度大于70mIU/L不会带来额外的益处(可能是由于肿瘤细胞中重组人促甲状腺激素的表达存在一定的阈值),因此可以缩短停用甲状腺激素的时间。

T.Zhao等人也报告说,低危和中危患者的甲状腺激素浓度需要大于30mIU/L,但该研究有其局限性:回顾性分析、I-131活性的变化(1.1–5.5GBq)、甲状腺激素小于30mIU/L的患者样本少、随访时间短[30]。

与上述研究相反,另一种观点认为甲状腺激素浓度不一定要大于30mIU/L。

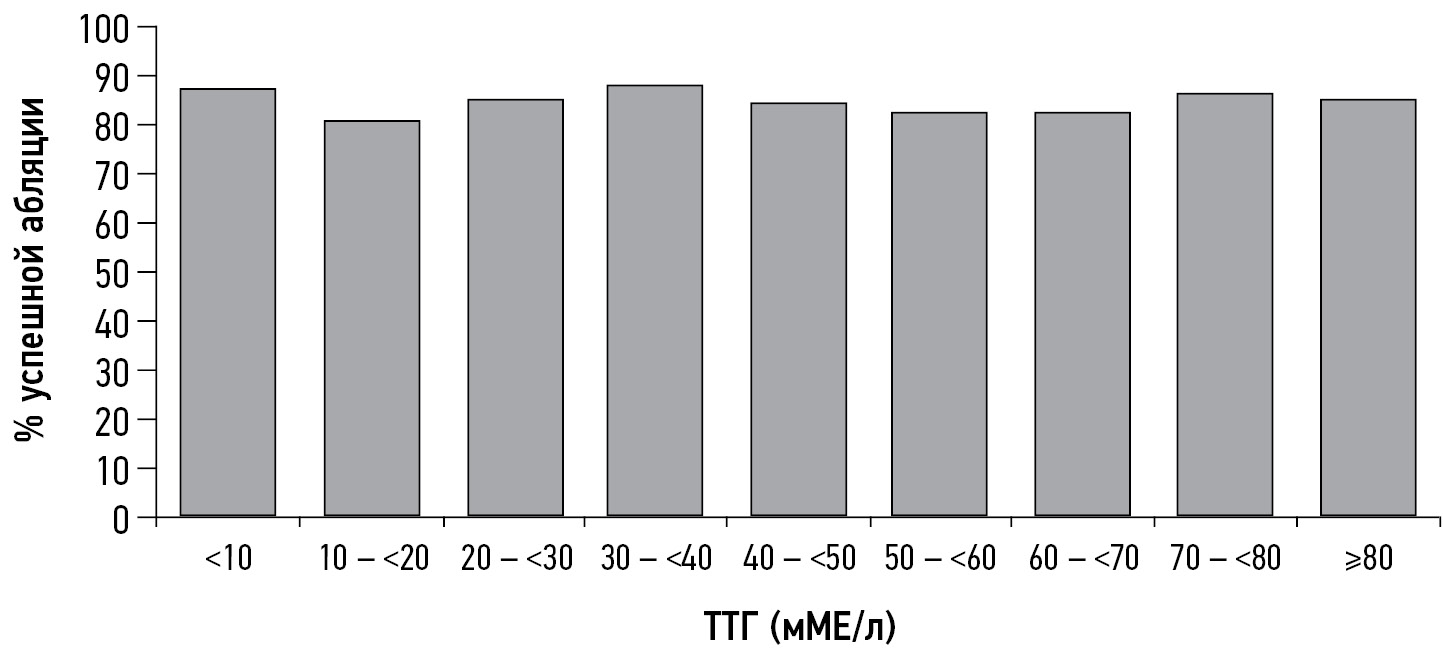

因此,Z.Hasbek等人在观察34例甲状腺激素浓度中位数为19.5±6.0mIU/L的患者和227例甲状腺激素浓度大于30mIU/L的患者时发现了,放射性碘治疗对第一组的1例患者和第二组的11例患者没有效果,这在统计学上没有意义。对治疗无反应的患者甲状腺球蛋白明显升高,并出现局部和远处转移。作者认为,甲状腺激素浓度并不是放射性碘治疗成功反应的唯一和绝对因素,而患者确诊时的年龄(大于45岁)、转移灶的存在、甲状腺球蛋白浓度和残留甲状腺组织的体积应被视为放射性碘治疗疗效不佳的可能标准[31]。德国的一个研究小组也得出了类似的结论:消融时的甲状腺激素水平对消融成功率、无复发生存率和肿瘤特异性死亡率没有影响(图1)[32]。

图1。与I-131治疗时甲状腺激素水平有关的成功消融患者比例。

在一项对1873例无远处转移证据的放射性碘治疗患者进行的回顾性分析中,甲状腺激素浓度对放射性碘治疗疗效、无复发生存率或高分化甲状腺癌相关死亡率没有显著的统计学影响。275例甲状腺激素小于30mIU/L的患者中有230例接受了放射性碘治疗,1598例甲状腺激素大于30mIU/L的患者中有1359例接受了放射性碘治疗。在消融时,对放射性碘治疗不完全反应有统计学意义的影响因素包括:

- I-131活性;

- 组织学特征;

- 患者性别;

- T期;

- 有无区域淋巴结转移;

- 甲状腺球蛋白浓度。

无转移灶、甲状腺球蛋白浓度低、肿瘤大小较小、I-131活性高和女性性别被认为是放射性碘治疗成功的独立因素。作者还指出,患者体内的甲状腺激素浓度受刺激的速度较慢:

- 患有转移性疾病;

- 年龄较大;

- 女性[32,33]。

由于这组患者的甲状腺激素浓度在3周后没有上升到公认的目标值(大于30mIU/L),因此不宜进一步延长停用甲状腺激素的时间。

N.Ju等人也得出了类似的结论(图2)。

图2。与I-131治疗时甲状腺激素水平有关的残留甲状腺组织成功消融患者比例。8个亚组中没有统计学意义。

甲状腺激素的缓慢刺激可能与雌激素对甲状腺激素β-亚基mRNA表达水平的影响有关,导致其在雌激素过多条件下受到抑制[35]。然而,甲状腺激素浓度的这一调节机制以及机体雌激素状态对 高分化甲状腺癌发生和发展的影响理论尚未完全清楚,需要进一步研究[36–38]。

因此,有许多因素可能会严重影响放射性碘治疗在高分化甲状腺癌中的成功应用。这些因素需要引起重视并进行个体化治疗,而“目标”甲状腺激素浓度大于30mIU/L的首要作用实际上可能被夸大了。关于在甲状腺激素浓度小于30mIU/L的情况下进行放射性碘治疗的研究,将改变目前对放射性碘治疗准备工作的看法,使其朝着更安全且疗效相当的方向发展。

重组人促甲状腺激素Α

1987年,从中国仓鼠卵巢FRTL-5细胞培养的人类甲状腺激素中获得了重组人促甲状腺激素。1998年,美国批准使用重组人促甲状腺激素,2001年,欧洲批准使用重组人促甲状腺激素作为放射性碘诊断测试的准备。后来,重组人促甲状腺激素又被批准作为停用甲状腺激素的替代品,为患者进行放射性碘治疗准备:

- 在欧洲:自2005年起;

- 在美国:自2007年起;

- 在俄罗斯:自2018年起。

在许多研究中,作为术后放射性碘治疗的准备,重组人促甲状腺激素的疗效与停用甲状腺激素的疗效相当[39–43]。然而,重组人促甲状腺激素能否作为放射性碘治疗的一部分用于甲状腺癌复发高危患者和远处转移灶的治疗仍是一个悬而未决的问题。在此之前,曾有多例高危患者在使用重组人促甲状腺激素准备放射性碘治疗时效果不佳,而在停用甲状腺激素的情况下重复放射性碘治疗疗程则获得了成功[44–46]。

重组激素与内源性激素的作用不同是假定的机制之一,这是因为重组激素分子的唾液酸饱和程度更高、甲状腺激素受体的糖基化程度不同,以及随着放射性碘治疗疗程的增加可能出现肿瘤的多克隆性[46]。

与30mIU/L的“临界点”相比,甲状腺激素对放射性药物摄取和治疗效果的剂量和时间依赖性影响(换言之,曲线下面积)更为显著。A.Vrachimis等人认为,这可能是限制使用重组人促甲状腺激素的因素之一[32]。

尽管如此,最近的数据表明,重组人促甲状腺激素不仅对低危和中危患者有效,对高危患者也同样有效。因此,J.Hugo等人对586名患者(其中321人的准备包括停用左甲状腺素钠的方法,265人的准备包括重组人促甲状腺激素应用)(包括复发的中危和高危人群)进行的回顾性研究显示了,在中位随访9年的长期临床结果中,两者并无差异。此外,在短期内(中位为2.5年),与使用重组人促甲状腺激素组相比,取消治疗组对初治放射性碘治疗的不完全反应概率更高(47%对39%,p=0.03),需要再次手术或放射性碘治疗疗程的发生率更高(37% 对 29%,P=0.05)。从经济角度来看,使用重组人促甲状腺激素有可能缩短持续和/或复发患者的积极动态随访期[41],降低国家的经济成本[47–51],包括在重组人促甲状腺激素成本降低30%的情况下实现经济效益的70%可能性[52]。

其他研究者也报告了类似的结果,即重组人促甲状腺激素对中危和高危人群的疗效至少相 当[53–59]。

目前,American Thyroid Association在其高分化甲状腺癌治疗指南中不建议在高复发风险患者中使用该药物[9]。Europe Association of Nuclear Medicine的指导方针允许对远处转移的患者进行off-label[8]。

使用重组人促甲状腺激素的副作用较少。在中枢神经系统转移瘤患者中使用该药物仍需谨慎,因为甲状腺激素的急性刺激可能会导致转移瘤的生长/增大和明显的临床症状[60]。

在一项对88名准备通过停用甲状腺激素和使用重组人促甲状腺激素(分别为51人和37人)进行放射性碘治疗的患者进行的研究中,10年生存率分别为62%和73%。因此,使用重组人促甲状腺激素与更差的治疗效果或预后无关[61]。

表2总结了使用重组人促甲状腺激素的主要优缺点及其目标患者群体。

表2。使用重组人促甲状腺激素α的优缺点及首选给药适应症

优势 | 缺点 | 目标群体 |

甲状腺功能减退的阶段水平测量是减少对某些危险器官副作用的机会; 与停药前后的患者相比,放射性碘治疗患者的生活质量更高; 缩短放射性碘治疗/诊断测试的准备时间; 降低唾液腺受损的风险; 降低整个身体的辐射负荷(由于肾小球滤过率没有变化)和骨髓损伤的风险; 缩短可能的住院时间 | 费用 泪腺导管病变的发病率较高; 缺乏关于在远处转移患者中使用的充分数据 | 年龄较大; 在甲状腺机能减退的背景下有恶化风险的靶器官慢性疾病(慢性心力衰竭、缺血性心脏病II级及以上、梗塞/中风病史、慢性阻塞性肺病、肝炎、类风湿性关节炎、糖尿病、慢性肾脏疾病、精神病、慢性胰腺炎、免疫缺陷状态等); 单肾/移植肾患者; 碳水化合物代谢障碍、肥胖症患者; 口腔感染/疾病患者、有唾液腺炎病史的患者、唾液腺导管内有结石的患者; 动脉高血压控制不佳; 非酒精性脂肪肝、失代偿期肝病 |

尽管对高危复发组使用重组人促甲状腺激素的意见不一,但其潜在优势可能是在短时间内更明显地增加 甲状腺激素。众所周知,转移瘤患者的钠碘同向转运体表达较低,这可能需要更高的甲状腺激素浓度来捕获肿瘤细胞中的I-131;此外,长期停用甲状腺激素进行准备可能会对肿瘤预后产生不利影响并导致病情进展[62–64]。

I.I.Dedov等人的一项研究[65]显示了,70%的患者在第二次注射重组人促甲状腺激素后甲状腺激素浓度大于100mIU/L,但目前还没有关于高危患者最佳甲状腺激素水平及其对疗效贡献的研究。

就对高危器官的影响而言,重组人促甲状腺激素比左甲状腺素钠停药的优势值得单独考虑,下文将进一步讨论。

使用不同准备方案的副作用,解决办法

在准备放射性碘治疗的过程中,停用甲状腺激素时的患者处于严重的医源性甲状腺功能减退阶段,伴随着生活质量的下降和靶器官副作用的发展。甲状腺激素受体不仅存在于甲状腺组织中,而且还存在于脂肪细胞、成纤维细胞、破骨细胞、白细胞、单核细胞以及心肌细胞、内皮细胞和血管平滑肌细胞(包括入球小动脉)的膜 上 [66]。

在心血管系统方面,需要注意以下几点:

- 射血分数下降;

- 静息时左心室舒张功能障碍;

- 外周血管总阻力增加;

- 内皮功能障碍。

所有这些都可能导致高血压患者高血压矫正的恶化[67]。由于肾脏滤过功能下降,肾上腺素、去甲肾上腺素和皮质醇的清除速度减慢[68]。两项研究报告同型半胱氨酸水平升高[69,70]。这些变化可能会导致心肾综合征的发生和发展。在服用抗凝剂的甲状腺切除患者中,左甲状腺素钠停药期间甲状腺激素水平与国际标准化比值之间存在反向相关性,这可能需要额外监测血液凝固系统参数,以便及时纠正治疗。

多次报告了对肝脏的负面影响:甲状腺激素停药患者的丙氨酸氨基转移酶和天门冬氨酸氨基转移酶活性升高[71,72],而使用重组人促甲状腺激素不会导致肝功能受损[71]。脂质代谢紊乱的方向是高密度脂蛋白失衡[67,73]。这是因为甲状腺激素的缺乏会导致高密度脂蛋白受体的表达减少[74],从而导致高密度脂蛋白浓度增加以及血浆总胆固醇总量增加[73]。甲状腺功能障碍与情感障碍之间存在着明确的联系[75]。与此同时,随着甲状腺功能减退程度的增加,疾病控制也会恶化,这可能与脑血流量减少以及弥漫性[76]和/或区域性[77]葡萄糖清除率降低有关。由于脑细胞缺乏从血液中获得足够的氧气和葡萄糖的能力,抑郁症的症状可能会加剧,抑郁症最常伴随着甲状腺功能减退[78]。

碳水化合物代谢受损的原因可能包括胃排空能力延长和肝脏葡萄糖转运能力降低,从而导致餐后和空腹血糖过低[79]。

有证据表明,甲状腺激素对免疫反应的调节有影响[80],这在甲状腺功能减退患者中可能会导致感染性疾病发病率上升。特别值得注意的是,许多研究[71,81–87]都证实了肾功能受到抑制,包括在取消左甲状腺素钠的背景下发生的抑制,但在使用重组人促甲状腺激素时则没有。一项研究报告说,在使用重组人促甲状腺激素期间,通过多普勒超声检查,肾脏灌注量减少。不过,该研究是在注射药物后第5天对小样本患者进行的[66]。

限碘饮食导致低钠血症的病例已有描述[88–91],风险因素包括:

- 高龄;

- 服用噻嗪类利尿剂;

- 长期限碘饮食;

- 长期甲状腺功能减退;

- 存在多处转移灶,这可能会导致抗利尿激素分泌不当综合征的发生,从而导致抗利尿激素过度增加[93,94]。

值得注意的是,低钠血症的一个常见原因是患者由于对限制碘饮食原理的认识不足而自行限制食盐。

在I.Horie等人的研究中,5%的患者出现高钾血症,其与年龄(60岁以上)和摄入血管紧张素转换酶抑制剂有关,这也可能与长期停用左甲状腺素钠期间肾功能受损有关[93]。

有趣的是,放射性碘治疗准备方法的选择也可能影响I-131暴露后副作用的频率和强度。例如,表达 钠碘同向转运体的器官能够积聚I-131,在某些情况下可能会导致其受损。

根据本中心的临床观察经验以及世界范围内的出版物,唾液腺占病变的20%–30%以上[94–97]。患者可能表现为味觉改变、感染、面部神经受累、口腔炎、念珠菌病。最初的症状通常是腺体阻塞性肿胀,这是由于在炎症过程中腺管管腔变窄所致。预防唾液腺炎症的方法有很多,包括使用拟胆碱药、催涎剂、细胞保护剂(氨磷汀)和唾液腺按摩,但效果并不明显[97–100]。此外,在放射性碘治疗后的第一天使用催涎剂会导致唾液腺的辐射剂量增加约28%,因此不建议在治疗后的第一天使用柠檬/吸吮糖果/其他催涎剂[99,102]。在未接受治疗的情况下,只有54%的患者在随访6年后不再患有慢性唾液腺炎[100],这说明有必要寻找新的措施来预防唾液腺炎。

在A.Trukhin等人的研究中,与4周取消左甲状腺素钠相比,使用重组人促甲状腺激素与观察到泪管中累积放射性药物的频率较高有关[102]。根据其他学者的研究,使用重组人促甲状腺激素可使放射性碘治疗后急性唾液腺炎的病例数减少约20%[103],这可能只占第二年的6.7%[104]。

在放射性碘治疗的副作用中,消融术后继发性白血病的发生虽未得到广泛报道,但我们认为需要特别关注。我们对148215名患者进行了分析;与单纯接受手术治疗的患者相比,因分化型甲状腺癌而接受原发性放射性碘治疗的患者在最初3年中罹患急性和慢性骨髓性白血病的风险更高,且具有显著的统计学意义。虽然急性骨髓细胞白血病的风险在放射性碘治疗术后3年迅速下降到基线,但慢性骨髓细胞白血病的风险在10年内仍然很高[105]。

另一个模棱两可的结论是,在指定I-131放射性药物活性低剂量后,患者体内稳定染色体畸变的数量增加,与使用重组人促甲状腺激素相比,使用左甲状腺素钠取消治疗的患者持续时间更 长[106]。临床解释所获得的结果需要更长时间的随访和对因果关系的详细研究。

因此,在放射性碘治疗的准备阶段以及随访期间,临床医生可能应更加警惕存在以下情况的患者:

- 高血压症;

- 免疫缺陷;

- 中度肝功能和/或肾功能损伤;

- 电解质和/或碳水化合物紊乱;

- 情感障碍;

- 其他先前描述过的情况。

优先在有甲状腺功能减退症并发症的易感患者中使用重组人促甲状腺激素,并在放射性碘治疗期间对他们进行限碘饮食和遵守治疗方法的基本原则教育是预防与甲状腺功能减退症相关的易感器官副作用的发生并降低其严重程度的方法之一。

限碘饮食

根据迄今为止积累的数据,人们认为肿瘤细胞和未改变的甲状腺癌细胞摄取碘的程度由几个因素决定:

- 残留甲状腺组织的数量;

- 甲状腺激素充分刺激;

- 钠碘同向转运体表达;

- 治疗时的中位碘浓度[107]。

根据早期研究,限碘饮食后患者残留甲状腺组织对碘的吸收增加了2-3倍[108,109],这可能会影响放射性碘治疗的疗效。大多数科学界对患者准备接受放射性碘治疗遵循以下标准:最佳碘排泄水平(UIE)小于50μg/L[8–10],充足碘排泄水平小于100μg/L [8]。然而,对于限碘饮食的持续时间和强度并没有明确的标准。

为了寻找是否需要遵守限制碘饮食的问题的答案,已经进行了多项研究,其中包括J.Tala等人的研究。他们的研究在科学界引起了一些不和谐的声音。作者发现尿碘水平与放射性碘治疗的效果之间没有相关性,而且尿碘水平大于100μg/L和小于100μg/L的患者组之间也没有差异。不过,需要考虑的是,该研究是在中度缺碘地 区(意大利锡耶纳)进行的,没有足够的体内碘含量高的患者样本,而且I-131放射性剂量不同,这可能导致放射性碘治疗的临床效果比中度缺碘的影响更大[110]。

事实上,患者体内的碘含量达到多少才算为放射性碘治疗做好了充分准备,这个问题仍然存在争议。

因此,M.Lee等人的研究发现了,放射性碘治疗对中度和轻度缺碘人群的疗效没有差 别[111]。A.E.Tobey等人的研究表明了,碘水平低于50/100/150mg/天的组间放射性碘治疗的疗效无明显差异,但尿碘浓度大于200mg/天的患者疾病进展的风险更高。

下一个相关问题是饮食所需的持续时间。最常见的建议期限是1–2周,但各国的限碘饮食方法和方案各不相同。由于不同地区的碘供应情况不同,因此无法明确规定饮食的时间和强度。为期两周的限碘饮食可能会影响患者的生活质量、社会功能和低钠血症风险。然而,在碘摄入过量的地区,2周时间可能更适合达到充足的消融前体内碘水平[107,115–117]。对患者进行有关限碘饮食基本方面的充分教育是一个重要的考虑因素。例如,在与营养师/营养学家或营养护士合作提供最低限度患者教育的研究中,有研究报告说,在提供3–7天菜单的情况下,与基线相比,碘减少百分比的结果更好[112,117–119]。

在中度缺碘或碘摄入充足的地区进行的研究表明了,限碘饮食一周后,碘摄入量达到最佳水 平[118,120],而根据M.J.Pluijmen等人和B.L.Dekker等人的研究,4天后达到最佳水平[113,121]。在碘摄入量高的地区进行的一些研究也显示了为期一周的限碘饮食的效果[111,112,118,119]。

许多研究都存在局限性,除了A.E.Tobey等 人[112]的研究之外,其他许多研究都是针对中危和低危患者进行的,因此无法对高危患者的短期和长期结果进行全面评估。值得注意的是,在中度碘缺乏的国家(如意大利)进行的研究中,尿碘含量的中位数为95μg/L,停用左甲状腺素钠的患者的差异从25μg/L到1890μg/L不等,这在个别情况下可能会影响治疗效果。值得注意的是,在本研究中,由于该地区的缺碘状况,没有为患者规定限碘饮食,高危患者被排除在分析之外。

在放射性碘治疗之前调查患者的碘状况是个性化治疗的方法之一。在每个病例中,包括复发/进展风险高的病例,都应特别注意在放射性碘治疗之前达到最佳的碘库,因为准备治疗过程中的每个因素,包括碘状况,都会影响治疗的成功。表3重点介绍了有关这一主题的主要研究。

表3。不同地区碘状况国家的限碘饮食特点及其效果比较

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

研究 | 患者样本(详情) | 低碘饮食的特点 | 指导 | 估算碘浓度/评估放射性碘治疗效果的方法 | 结果(对放射性碘治疗结果的影响、体内碘库减少的百分比) | 研究的局限性 |

巴西;中高碘摄入量 | ||||||

R.P.Padovani等人,2015年[122] | n=125* | 低碘饮食:15天,n1=79; 低碘饮食:30天,n2=46 | + | 24-UIE | n1:中位数=99mg/L(减少60%); n2:中位数=80mg/L(减少70%) | *大多数患者因难以遵循方案而被排除在外(基线:n=306) |

韩国;碘摄入过量 | ||||||

S.U.Sohn等人,2013年[107] | n=295 (碘-131单次活性:1100MBq) | 低碘饮食:2周 | +++ | 伴有肌酐校正的单个尿样UIE | 成功消融率:74.9%(221/295); UIE小于66mg/g(碘/肌酐比值)组的效果优于UIE大于66mg/g组: 81%对67%,p=0.03; UIE大于250mg/g组的结果明显较低(p<0.05) | 回顾性分析; 排除了可能影响放射性碘治疗结果统计的远处转移和颈部淋巴结转移患者,不考虑到甲状腺球蛋白抗体 |

I.D.K.S.Yoo等人,2012年[115] | n=161: n1(严格低碘饮食)=90; n2(中度低碘饮食)=71 | 严格低碘饮食/中度低碘饮食:2周 | ++ | UIE未测量 | 成功的放射性碘治疗:严格低碘饮食——75,8%, 中度低碘饮食——80,3%(р=0,48) | 排除了远处转移的患者; 没有关于接受甲状腺激素α准备患者的信息 |

H.K.Kim等人,2011年[118] | n=19(取消左甲状腺素钠) | 严格低碘饮食:2周 | +++ | 伴有肌酐校正的单个尿样UIE:每天,14天 | 碘/肌酐比值: 第0→7天:↓从576到26μg/g; 第0→14天:↓小于19,6μg/g; 第3天:95%的碘/肌酐小于150mg/g 第6天:95%的碘/肌酐小于66μg/g | 采用单个尿样评估碘排泄量; 研究结果不适用于缺碘地区; 未评估消融效果 |

C.Y.Lim等人,2015年[117] | n=101: n1(严格低碘饮食)=47; n2(中度低碘饮食)=54 | 严格低碘饮食/中度低碘饮食:4周 | ++ | 第2周和第4周伴有肌酐校正的24-UIE | n1和n2之间没有统计学差异。 碘/肌酐比值: 第2周——28.6μg/g; 第4周——35.0μg/g。 两组在第2周和第4周的碘-131吸收率没有差异 | 未对放射碘治疗的短期和长期疗效进行评估 |

M.Lee等人2014年[111] | n=195 | 低碘饮食:2周 | +++ | 第1周和第2周的24-UIE | 第1周:中位数=12,8μg/L,87,2%的UIE小于50μg/L; 第2周:中位数=13,4μg/L,92,3%的UIE小于50μg/L 成功消融率:82,4%;中度和轻度缺碘组没有差异 | 不同的治疗活性(3700–7400MBq); 无高危患者 |

续表1

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

意大利;中度缺碘水平 | ||||||

J.Tala等人,2010年[110] | n=201 (n1=25,左甲状腺素钠取消4周; n2=76,接受重组人促甲状腺激素治疗) | 未进行 | – | 单个尿样中的UIE | 成功消融率:84.6%(UIE:中位数=104μg/L,25至1890μg/L)。 完全反应组(中位数=104μg/L)和不完全反应组(中位数=104μg/L,25至851μg/L)之间没有统计学差异。 UIE小于100μg/L组和大于100μg/L组对治疗的反应没有差异(p=0.98) | 回顾性分析; 尿碘浓度高的患者样本较少; 消融时碘-131活性水平不同(1100-5550MBq); 无对照组,高复发组 |

荷兰;充足的碘摄入量 | ||||||

M.J.Pluijmen等人,2003年[113] | n=120: n(低碘饮食)=59; n(正常饮食)=61 | 低碘饮食:4天 | +++ | 24-UIE: n(正常饮食)——9名患者; n(低碘饮食)——60名患者 | n(低碘饮食):UIE平均值——27μg/天。 n(正常饮食):UIE平均值——159μg/天。 低碘饮食组在甲状腺区域的碘捕获率更高(5.1±3.8%对3.1±2.5%,p<0.001)。 低碘饮食组与正常饮食组相比,疗效更高(分别为71%和45%) | 回顾性分析; 不包括有转移灶的患者 |

B.L.Dekker等人,2022年[123] | n=65 | 未进行 | +++ | 第4天和第7天的24-UIE | 第4天:72.1%的24-UIE小于50μg,UIE平均值——36.1μg; 第7天:82.0%的24-UIE小于50μg (p=0.18),UIE平均值——36.5μg | 这些研究可能不适用于碘摄入量高的国家; 未对初始尿碘水平进行评估 |

美国;从中到高碘摄入量 | ||||||

L.F.Morris人,2001年[116] | n=94: n(低碘饮食)=44; n(正常饮食)=50 | 低碘饮食:10–14天 正常饮食:限制碘制剂、加碘盐、海产品 | ++ | 单个尿样中的UIE(7名低碘饮食患者和7名正常饮食患者) | 消融成功率:68.2%(低碘饮食)与62%(正常饮食),p=0.53。有转移灶的患者:分别为80.0%和66.7%。 n(低碘饮食):碘减少69.4%(UIE平均值——567.7μg/L→173.9μg/L); n(正常饮食):碘减少23.6%(UIE平均值——444.0μg/L→498.9μg/L) | 不同的治疗活性(3700–7400MBq); 尿碘筛查的患者样本较少; 甲状腺球蛋白、甲状腺球蛋白抗体水平未纳入消融标准 |

A.E.Tobey等人,2018 [114] | n=70: n1(重组人促甲状腺激素)=16; n2(取消左甲状腺素钠)=54 | 低碘饮食:2天 | +++ | 24-UIE | 21%的患者病情恶化;UIE大于200μg/天的患者风险更高。 UIE为50、100、150μg/天组之间没有差异 | 回顾性研究; 小样本; 放射性碘治疗时的碘-131活性为1.1至11.1GBq; 随访期——3.7年 |

J.T. Park 等人,2004 [125] | n=36 | n1=15:2周左甲状腺素钠+2周低碘饮食; n2=21:2周低碘饮食,不含左甲状腺素钠 | + | 1周和2周后伴有肌酐校正的单个尿样UIE,按 Cr | 碘/肌酐比值: n1:中位数(1周)=76.91μg/g (21%UIE小于50;71%小于100μg/g); n2:中位数(1周)=26.16μg/g(78%小于50μg/g),p<0.001 低碘饮食2周后的UIE在第1组和第2组中没有差异(p<0.15) | 未对放射性碘治疗的短期和长期疗效进行评估 |

表1结束

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

日本;碘摄入过量 | ||||||

S.Ito等人,2018年[118] | n=45 碘-131单一活性:1100MBq) | 低碘饮食:2周 (严格低碘饮食:n=12; 低碘饮食:n=25) | +++ | 伴有肌酐校正的单个尿样UIE | UIE(碘/肌酐比值): 饮食前和饮食后的中位数:分别为286μg/g(范围为40-7100μg/g)和74μg/g(范围为16-816μg/g)。 全部样本中有56%成功消融 | 小样本; 根据无甲状腺球蛋白、甲状腺球蛋白抗体的闪烁扫描结果评估放射性碘治疗的疗效。 排除了M1患者; 对中度/充足碘摄入量的地区难以解释 |

C.Tomoda等人,2005年[121] | n=252: n1(中度低碘饮食)=220 n2(低碘饮食)=15 n3(严格低碘饮食)=17 | 中度低碘饮食:1周 低碘饮食:1周 严格低碘饮食:2周 | + | 伴有肌酐校正的单个尿样UIE | n3(严格低碘饮食): 碘/肌酐中位数:130μg/g(范围为23–218μg/g) n1(中度低碘饮食): 碘/肌酐中位数:125μg/g(范围为13–986μg/g),(p<0.01) 碘/肌酐比值小于100μg/g:26%(n1)和70%(n3) | 未对放射性碘治疗的短期和长期疗效进行评估; 通过单一尿样评估碘含量(非“金标准”) |

马来西亚:中度缺碘水平 | ||||||

W.F.Sohaimi等人,2019年[122] | n=104(取消左甲状腺素钠) | 严格低碘饮食/中度低碘饮食:1周 | + | 单个尿样中的UIE | 第0→7天:89.1%(严格低碘饮食)和91.8%(中度低碘饮食)的UIE小于100μg/L 中度低碘饮食: UIE平均值:89.24μg/L→56.85μg/L(↓36.3%) 严格低碘饮食: UIE平均值:107.8μg/L→63.82μg/L(↓40.8%) | 未对放射碘治疗的短期和长期疗效进行评估 |

注:

“-”——没有任何指导

“+”——印刷说指导

“++”——印刷和口头指导

“+++”——印刷、口头指导、医务人员培训

UIE——尿碘排泄量;24-UIE——每日尿碘排泄量;UIE平均值——尿碘平均值

在考虑采用更严格或不太严格的限碘饮食方案时,无论是在碘减少的程度上,还是在放射性碘治疗的疗效上,都没有发现明确的令人信服的数据支持严格的饮食方案,而更严格的方案可能更容易导致患者生活质量下降和心理不适。因此,具体训练方案的选择将取决于特定中心对患者的宣传/教育能力、是否存在合并病症以及该地区最初的碘状况。

2020年的《俄罗斯临床建议》提到了为期两周的限碘饮食。考虑到本地区的碘状况和世界惯例的数据,限碘饮食的持续时间可缩短至4–7天。

结论

迄今为止,专家们对于低危和中危复发患 者(占高分化甲状腺癌患者的大多数)辅助放射性碘治疗的适应症仍然意见不一。使用放射性碘治疗会给患者带来潜在的并发症风险,因此需要逐例评估临床获益,而这只能通过对甲状腺癌复发进行动态风险分层来实现。在该方法80年的历史中,文献报道的研究表明,准备和治疗高分化甲状腺癌的方案具有异质性,这也形成目前对放射性碘治疗的看法。

对于低危/中危患者,甲状腺激素水平夏鸥30mIU/L的甲状腺功能减退患者的放射性碘治疗可能会抵消甲状腺功能减退和相关并发症带来的风险。迄今为止,关于消融前甲状腺激素水平是否需要大于30mIU/L,以及停用左甲状腺素钠两周(相对于四周)对诱导甲减状态的疗效的研究虽然有限,但在方法学上是可靠的。还需要进一步研究,才能将结果推断到高危患者群体中。从理论上讲,可能需要更高水平的甲状腺激素来刺激低碘饮食并提高治疗质量。用于这类患者的首选药物是重组人促甲状腺激素,但需要研究其药代动力学特征对放射性碘治疗疗效的影响。此外,重组人促甲状腺激素目前的供应受到其高昂成本的限制,因此有必要降低其在俄罗斯联邦的生产技术成本,并重新考虑向有需要的患者群体提供该药物。

为了提高放射性碘治疗的疗效,个体化治疗方法中的一个步骤可以是在放射性碘治疗前测量单个尿样中的碘浓度,以评估患者对限制碘饮食的依从性并预测治疗的有效性。根据B.L.Dekker等人的建议[126],可以通过测量唾液中的碘浓度来简化程序。然而,尽管该方法与金标准(每日尿液中的碘)具有同等信息量,但仍需要验证,并存在一定的局限性。作为标准病理形态学检查的一部分,测定低碘饮食表达水平可预测对放射性碘治疗的反应,这也可能影响I-131的治疗活性,从而为患者的管理做出重要贡献。

所使用的I-131治疗活性范围很广,这是有关放射性碘治疗准备的研究的重要限制因素之一,会影响对综合疗效的最终评估,在仔细研究该出版物所涉及的问题时应考虑到这一点。

为了开发更精确、更个性化的放射性碘治疗方法,必须了解许多复杂的机制,包括患者的个体特征、肿瘤生物学特性以及这种治疗方式的疗效和安全性所依赖的其他因素。为了最大限度地减少不良反应,必须对将从这种干预中受益的患者进行仔细取样。放射性碘治疗处方的合理性问题需要单独关注和进一步研究。

总结了目前对放射性碘治疗准备工作的看法和趋势,这是一项大有可为的工作:

- 让患者了解疾病、放射性碘治疗准备、治疗后制度和动态随访,以提高生活质量;

- 根据地区的碘状况,将限碘饮食时间缩短至4–7天,或完全放弃严格的饮食限制,或在限碘饮食期间扩大饮食方案,并将消融前最佳碘水平的“阈值”降至100–150μg/L;

- 考虑在甲状腺激素浓度小于30mIU/L,通过将左甲状腺素钠取消期缩短至2周,对某些患者群体(复发风险低/中等)进行放射性碘治疗的可能性;

- 扩大重组人促甲状腺激素的适应症,包括复发风险高的患者和有严重并发症的患者。

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Funding source. This work was conducted within the fund of the State Assignment «Study of pharmacosafety of theranostic radiopharmaceuticals using hybrid molecular imaging in the diagnosis and treatment of endocrine and oncological diseases in children and adults». Registration number 123021000041-6.

Competing interests. The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contribution. All authors made a substantial contribution to the conception of the work, acquisition, analysis, interpretation of data for the work, drafting and revising the work, final approval of the version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. M.V. Reinberg — contribution to the concept of the paper, design of the review, collection and processing of materials, analysis of the obtained data and writing the text; K.Yu. Slashchuk — assistance in collection and processing of materials, data analysis, making substantial revisions to the manuscript to improve the scientific value of the article; approval of the final version of the manuscript; A.A. Trukhin — text editing, data analysis, adding valuable comments to improve the scientific value of the article; K.I. Avramova — assistance in collection and processing of materials, text editing; M.S. Sheremeta — adding valuable comments, approval of the final version of the manuscript.

作者简介

Maria V. Reinberg

Endocrinology Research Centre

编辑信件的主要联系方式.

Email: mrezerford12@gmail.com

ORCID iD: 0009-0002-1632-2197

Researcher ID: IUO-4237-2023

俄罗斯联邦, Moscow

Konstantin Y. Slashchuk

Endocrinology Research Centre

Email: slashuk911@gmail.com

ORCID iD: 0000-0002-3220-2438

SPIN 代码: 3079-8033

MD, Cand. Sci. (Med.)

俄罗斯联邦, MoscowAlexey A. Trukhin

Endocrinology Research Centre

Email: Alexey.trukhin12@gmail.com

ORCID iD: 0000-0001-5592-4727

SPIN 代码: 4398-9536

Cand. Sci. (Engin.)

俄罗斯联邦, MoscowKarina I. Avramova

Endocrinology Research Centre

Email: dravramovak@gmail.com

ORCID iD: 0009-0008-4970-8911

SPIN 代码: 4330-0263

俄罗斯联邦, Moscow

Marina S. Sheremeta

Endocrinology Research Centre

Email: marina888@yandex.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0003-3785-0335

SPIN 代码: 7845-2194

MD, Cand. Sci. (Med.)

俄罗斯联邦, Moscow参考

- Vanushko VE, Tsurkan AYu. Treatment of differentiated thyroid cancer: cureunt statement of the problem. Clinical and experimental thyroidology. 2010;6(2):24–33. (In Russ). doi: 10.14341/ket20106224-33

- Kaprin AD, Starinskii VV, Shakhzadova AO, editors. Zlokachestvennye novoobrazovaniya v Rossii v 2021 godu (zabolevaemost’ i smertnost’). Moscow: MNIOI im. P.A. Gertsena −of NMRRC of the Ministry of Health of Russia; 2022. (In Russ).

- Durante C, Haddy N, Baudin E, et al. Long-term outcome of 444 patients with distant metastases from papillary and follicular thyroid carcinoma: benefits and limits of radioiodine therapy. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2006;91(8):2892–2899. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2838

- Cancer Stat Facts: Thyroid Cancer [Internet]. National Cancer Institute: Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. [cited 2023 Sep 1]. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/thyro.html

- Braverman LE, Cooper DS, Kopp P. Werner & Ingbar’s The Thyroid: A Fundamental and Clinical Text. 11th ed.. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2021.

- Hassan A, Razi M, Riaz S, et al. Survival Analysis of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma in Relation to Stage and Recurrence Risk: A 20-Year Experience in Pakistan. Clinical Nuclear Medicine. 2016;41(8):606–613. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000001237

- Well-differentiated thyroid cancer. Clinical guidelines. ID 329. Approved by the Scientific and Practical Council of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. 2020. Available from: https://cr.minzdrav.gov.ru/recomend/329_1 (In Russ)

- Avram AM, Giovanella L, Greenspan B, et al. SNMMI Procedure Standard/EANM Practice Guideline for Nuclear Medicine Evaluation and Therapy of Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: Abbreviated Version. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2022;63(6):15N–35N.

- Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: The American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid. 2016;26(1):1–133. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0020

- Pacini F, Fuhrer D, Elisei R, et al. 2022 ETA Consensus Statement: What are the indications for post-surgical radioiodine therapy in differentiated thyroid cancer? European Thyroid Journal. 2022;11(1). doi: 10.1530/etj-21-0046

- Filetti S, Durante C, Hartl D, et al. Thyroid cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annals of Oncology. 2019;30(12):1856–1883. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz400

- Perros P, Boelaert K, Colley S, et al. Guidelines for the management of thyroid cancer. Clinical Endocrinology. 2014;81 Suppl. 1:1–122. doi: 10.1111/cen.12515

- Haddad RI, Bischoff L, Ball D, et al. Thyroid Carcinoma, Version 2.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2022;20(8):925–951. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2022.0040

- Golger A, Fridman TR, Eski S, et al. Three-week thyroxine withdrawal thyroglobulin stimulation screening test to detect low-risk residual/recurrent well-differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation. 2003;26(10):1023–1031. doi: 10.1007/bf03348202

- Davids T, Witterick IJ, Eski S, et al. Three-Week Thyroxine Withdrawal: A Thyroid-Specific Quality of Life Study. The Laryngoscope. 2006;116(2):250–253. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000192172.61889.43

- Lee J, Yun MJ, Nam KH, et al. Quality of life and effectiveness comparisons of thyroxine withdrawal, triiodothyronine withdrawal, and recombinant thyroid-stimulating hormone administration for low-dose radioiodine remnant ablation of differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid. 2010;20:173–179. doi: 10.1089/thy.2009.0187

- Leboeuf R, Perron P, Carpentier AC, Verreault J, Langlois MF. L-T3 preparation for whole-body scintigraphy: a randomized-controlled trial. Clinical Endocrinology. 2007;67(6):839–844. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02972.x

- Rajamanickam S, Chaukar D, Siddiq S, Basu S, D’Cruz A. Quality of life comparison in thyroxine hormone withdrawal versus triiodothyronine supplementation prior to radioiodine ablation in differentiated thyroid carcinoma: a prospective cohort study in the Indian population. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 2021;279(4). doi: 10.1007/s00405-021-06948-6

- Luna R, Penín M, Seoane I, et al. ¿Es necesario suspender durante 4 semanas el tratamiento con tiroxina antes de la realización de un rastreo-ablación? Endocrinología y Nutrición. 2012;59(4):227–231. (In Spanish). doi: 10.1016/j.endonu.2012.02.004

- Dow KH, Ferrell BR, Anello C. Quality-of-life changes in patients with thyroid cancer after withdrawal of thyroid hormone therapy. Thyroid. 1997;7(4):613–619. doi: 10.1089/thy.1997.7.613

- Liel Y. Preparation for radioactive iodine administration in differentiated thyroid cancer patients. Clinical Endocrinology. 2002;57(4):523–527. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2002.01631.x

- Piccardo A, Puntoni M, Ferrarazzo G, et al. Could short thyroid hormone withdrawal be an effective strategy for radioiodine remnant ablation in differentiated thyroid cancer patients? European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 2018;45(7):1218–1223. doi: 10.1007/s00259-018-3955-x

- Santos PA, Flamini ME, Mourato FA, et al. Is a four-week hormone suspension necessary for thyroid remnant ablation in low and intermediate risk patients? A pilot study with quality-of-life assessment. Brazilian Journal of Radiation Sciences. 2022;10(4):1–16. doi: 10.15392/2319-0612.2022.2047

- Cooper DS, Doherty GM, Haugen BR, et al. Revised American thyroid association management guidelines for patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2009;19(11):1167–1214. doi: 10.1089/thy.2009.0110

- Rosário PW, Vasconcelos FP, Cardoso LD, et al. Managing thyroid cancer without thyroxine withdrawal. Arquivos Brasileiros de Endocrinologia & Metabologia. 2006;50(1):91–96. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27302006000100013

- Edmonds CJ, Hayes S, Kermode JC, Thompson BD. Measurement of serum TSH and thyroid hormones in the management of treatment of thyroid carcinoma with radioiodine. The British Journal of Radiology. 1977;50(599):799–807. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-50-599-799

- Giovanella L, Piccardo A. A “new/old method” for TSH stimulation: could a third way to prepare DTC patients for 131I remnant ablation possibly exist? European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 2015;43(2):221–223. doi: 10.1007/s00259-015-3245-9

- Semenov DYu, Boriskova ME, Farafonova UV, et al. Prognostic value of Sodium-Iodide Symporter (NIS) in differentiated thyroid cancer. Clinical and experimental thyroidology. 2015;11(1):50. (In Russ). doi: 10.14341/ket2015150-58

- Xiao J, Yun C, Cao J, et al. A pre-ablative thyroid-stimulating hormone with 30-70 mIU/L achieves better response to initial radioiodine remnant ablation in differentiated thyroid carcinoma patients. Scientific Reports. 2021;11(1). doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-80015-8

- Zhao T, Liang J, Guo Z, Li T, Lin Y. In Patients with Low- to Intermediate-Risk Thyroid Cancer, a Preablative Thyrotropin Level of 30 μIU/mL Is Not Adequate to Achieve Better Response to 131I Therapy. Clinical Nuclear Medicine. 2016;41(6):454–458. doi: 10.1097/rlu.0000000000001167

- Hasbek Z, Turgut B. Is Very High Thyroid Stimulating Hormone Level Required in Differentiated Thyroid Cancer for Ablation Success? Molecular Imaging and Radionuclide Therapy. 2016;25(2):79–84. doi: 10.4274/mirt.88598

- Vrachimis A, Riemann B, Mäder U, Reiners C, Verburg FA. Endogenous TSH levels at the time of 131I ablation do not influence ablation success, recurrence-free survival or differentiated thyroid cancer-related mortality. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 2016;43(2):224–231. doi: 10.1007/s00259-015-3223-2

- Montesano T, Durante C, Attard M, et al. Age influences TSH serum levels after withdrawal of l-thyroxine or rhTSH stimulation in patients affected by differentiated thyroid cancer. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2007;61(8):468–471. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2007.04.001

- Ju N, Hou L, Song H, et al. TSH ≥30 mU/L may not be necessary for successful 131I remnant ablation in patients with differentiated thyroid cancer. European Thyroid Journal. 2023;12(4). doi: 10.1530/ETJ-22-0219

- Ren B, Zhu Y. A New Perspective on Thyroid Hormones: Crosstalk with Reproductive Hormones in Females. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022;23(5):2708. doi: 10.3390/ijms23052708

- Rubio GA, Catanuto P, Glassberg MK, Lew JI, Elliot SJ. Estrogen receptor subtype expression and regulation is altered in papillary thyroid cancer after menopause. Surgery. 2018;163(1):143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2017.04.031

- Derwahl M, Nicula D. Estrogen and its role in thyroid cancer. Endocrine-Related Cancer. 2014;21(5):T273–T283. doi: 10.1530/erc-14-0053

- Rajoria S, Suriano R, Shanmugam A, et al. Metastatic phenotype is regulated by estrogen in thyroid cells. Thyroid. 2010;20(1):33–41. doi: 10.1089/thy.2009.0296

- Tala H, Robbins R, Fagin JA, Larson SM, Tuttle RM. Five-year survival is similar thyroid cancer patients with metastases prepared for radioactive iodine therapy with either thyroid hormone withdrawal or recombinant human TSH. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2011;96(7):2105–2111. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0305

- Rosario PW, Mourão GF, Calsolari MR. Recombinant human TSH versus thyroid hormone withdrawal in adjuvant therapy with radioactive iodine of patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma and clinically apparent lymph node metastases not limited to the central compartment (cN1b). Archives of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2017;61(2):167–172. doi: 10.1590/2359-3997000000247

- Hugo J, Robenshtok E, Grewal R, Larson S, Tuttle RM. Recombinant human thyroid stimulating hormone-assisted radioactive iodine remnant ablation in thyroid cancer patients at intermediate to high risk of recurrence. Thyroid. 2012;22(10):1007–1015. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.0183

- Robenshtok E, Tuttle RM. Role of Recombinant Human Thyrotropin (rhTSH) in the Treatment of Well-Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Indian Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2012;3(3):182–189. doi: 10.1007/s13193-011-0115-1

- Higuchi CRS, Fernanda P, Jurnior PA, et al. Clinical Outcomes After Radioiodine Therapy, According to the Method of Preparation by Recombinant TSH vs. Endogenous Hypothyroidism, in Thyroid Cancer Patients at Intermediate-High Risk of Recurrence. Frontiers in Nuclear Medicine. 2021;1. doi: 10.3389/fnume.2021.785768

- Lawhn-Heath C, Flavell RR, Chuang EY, Liu C. Failure of iodine uptake in microscopic pulmonary metastases after recombinant human thyroid-stimulating hormone stimulation. World Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2020;19(1):61–64. doi: 10.4103/wjnm.WJNM_29_19

- Lee H, Paeng JC, Choi H, et al. Effect of TSH stimulation protocols on adequacy of low-iodine diet for radioiodine administration. PLoS One. 2021;16(9):e0256727. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0256727

- Driedger AA, Kotowycz N. Two Cases of Thyroid Carcinoma That Were Not Stimulated by Recombinant Human Thyrotropin. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2004;89(2):585–590. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031650

- Mernagh P, Campbell S, Dietlein M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of using recombinant human TSH prior to radioiodine ablation for thyroid cancer, compared with treating patients in a hypothyroid state: The German perspective. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2006;155(3):405–414. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02223

- Mernagh P, Suebwongpat A, Silverberg J, Weston A. Cost-effectiveness of using recombinant human thyroid-stimulating hormone before radioiodine ablation for thyroid cancer: The Canadian perspective. Value in Health. 2010;13(3):180–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2009.00650.x

- Borget I, Bonastre J, Catargi B, et al. Quality of life and cost-effectiveness assessment of radioiodine ablation strategies in patients with thyroid cancer: results from the randomized phase III ESTIMABL trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2015;33(26):2885–2892. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.6722

- Nijhuis TF, van Weperen W, de Klerk JMH. Costs associated with the withdrawal of thyroid hormone suppression therapy during the follow-up treatment of well-differentiated thyroid cancer. Tijdschrift voor nucleaire geneeskunde. 1999;21:98–100.

- Vallejo JA, Muros MA. Cost-effectiveness of using recombinant human thyroid-stimulating hormone before radioiodine ablation for thyroid cancer treatment in Spanish hospitals. Revista Española de Medicina Nuclear e Imagen Molecular (English Edition). 2017;36(6):362–370. doi: 10.1016/j.remnie.2017.09.001

- Luster M, Felbinger R, Dietlein M, Reiners C. Thyroid hormone withdrawal in patients with differentiated thyroid carcinoma: a one hundred thirty-patient pilot survey on consequences of hypothyroidism and a pharmacoeconomic comparison to recombinant thyrotropin administration. Thyroid. 2005;15(10):1147–1155. doi: 10.1089/thy.2005.15.1147

- Rosario PW, Xavier AC, Calsolari MR. Recombinant human thyrotropin in thyroid remnant ablation with 131I in high-risk patients. Thyroid. 2010;20(11):1247–1252. doi: 10.1089/thy.2010.0114

- Iizuka Y, Katagiri T, Ogura K, Inoue M, et al. Comparison of thyroid hormone withdrawal and recombinant human thyroid-stimulating hormone administration for adjuvant therapy in patients with intermediate- to high-risk differentiated thyroid cancer. Annals of Nuclear Medicine. 2020;34(10):736-741. doi: 10.1007/s12149-020-01497-0

- Robbins RJ, Driedger A, Magner J; The U.S. and Canadian Thyrogen Compassionate Use Program Investigator Group. Recombinant human thyrotropin-assisted radioiodine therapy for patients with metastatic thyroid cancer who could not elevate endogenous thyrotropin or be withdrawn from thyroxine. Thyroid. 2006;16(11):1121–1130. doi: 10.1089/thy.2006.16.1121

- Tu J, Wang S, Huo Z, et al. Recombinant human thyrotropin-aided versus thyroid hormone withdrawal-aided radioiodine treatment for differentiated thyroid cancer after total thyroidectomy: a meta-analysis. Radiotherapy and Oncology. 2014;110(1):25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.12.018

- Ma C, Xie J, Liu W, et al. Recombinant human thyrotropin (rhTSH) aided radioiodine treatment for residual or metastatic differentiated thyroid cancer. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008302

- Wolfson RM, Rachinsky I, Morrison D, et al. Recombinant Human Thyroid Stimulating Hormone versus Thyroid Hormone Withdrawal for Radioactive Iodine Treatment of Differentiated Thyroid Cancer with Nodal Metastatic Disease. Journal of Oncology. 2016:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2016/6496750

- Klubo-Gwiezdzinska J, Burman KD, Van Nostrand D, et al. Treatment of metastatic thyroid cancer: relative efficacy and side effect profile of preparation by thyroid hormone withdrawal versus recombinant human thyrotropin. Thyroid. 2012;22(3):310–317. doi: 10.1089/thy.2011.0235

- Wolffenbuttel BH, Coppes MH, Bongaerts AH, Glaudemans AW, Links TP. Unexpected symptoms after rhTSH administration due to occult thyroid carcinoma metastasis. The Netherlands journal of medicine. 2013;71(5):253–256.

- Tsai HC, Ho KC, Chen SH, et al. Feasibility of Recombinant Human TSH as a Preparation for Radioiodine Therapy in Patients with Distant Metastases from Papillary Thyroid Cancer: Comparison of Long-Term Survival Outcomes with Thyroid Hormone Withdrawal. Diagnostics. 2022;12(1):221 doi: 10.3390/diagnostics12010221

- Goldberg LD, Ditchek NT. Thyroid carcinoma with spinal cord compression. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1981;245(9):953-954. doi: 10.1001/jama.1981.03310340043025

- Hoelting T, Tezelman S, Siperstein AE, Duh QY, Clark OH. Biphasic effects of thyrotropin on invasion and growth of papillary and follicular thyroid cancer in vitro. Thyroid. 1995;5(1):35–40. doi: 10.1089/thy.1995.5.35

- Pietz L, Michałek K, Waśko R, et al. Wpływ stymulacji endogennego TSH na wzrost resztkowej objetości tarczycy u chorych po całkowitej tyreoidektomii z powodu raka zróznicowanego tarczycy. Endokrynologia Polska. 2008;59:119–122. (In Polish)

- Dedov II, Rumyantsev PO, Nizhegorodova KS, et al. Recombinant human thyrotropin in radioiodine diagnostics and radioiodine ablation of patients with well-differentiated thyroid cancer: the first experience in Russia. Endocrine Surgery. 2018;12(3):128–139. (In Russ). doi: 10.14341/serg9806

- Saracyn M, Lubas A, Bober B, et al. Recombinant human thyrotropin worsens renal cortical perfusion and renal function in patients after total thyroidectomy due to differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2020;30(5):653–660. doi: 10.1089/thy.2019.0372

- Chaker L, Razvi S, Bensenor IM, et al. Hypothyroidism. Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 2022;8(1). doi: 10.1038/s41572-022-00357-7

- Ortiga-Carvalho TM, Sidhaye AR, Wondisford FE. Thyroid hormone receptors and resistance to thyroid hormone disorders. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2014;10(10):582–591. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2014.143

- Lien EA, Nedrebo BG, Varhaug JE, et al. Plasma total homocysteine levels during short-term iatrogenic hypothyroidism. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2000;85(3):1049–1053. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.3.6439

- Bicikova M, Hampl R, Hill M, et al. Steroids, sex hormone-binding globulin, homocysteine, selected hormones and markers of lipid and carbohydrate metabolism in patients with severe hypothyroidism and their changes following thyroid hormone supplementation. Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine. 2003;41(3):284–292. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2003.045

- Lee SJ, Lee HY, Lee WW, Kim SE. The effect of recombinant human thyroid stimulating hormone on sustaining liver and renal function in thyroid cancer patients during radioactive iodine therapy. Nuclear Medicine Communications. 2014;35(7):727–732. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0000000000000118

- Targher G, Montagnana M, Salvagno G, et al. Association between serum TSH, free T4 and serum liver enzyme activities in a large cohort of unselected outpatients. Clinical Endocrinology. 2008;68(3):481–484. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.03068.x

- Pearce EN, Wilson PW, Yang Q, Vasan RS, Braverman LE. Thyroid function and lipid subparticle sizes in patients with short-term hypothyroidism and a population-based cohort. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2008;93(3):888–894. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1987

- Ness GC, Lopez D, Chambers CM, et al. Effects of L-triiodothyronine and the thyromimetic L-94901 on serum lipoprotein levels and hepatic low-density lipoprotein receptor, 3-hydroxy-3- methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase, and apo A-I gene expression. Biochemical Pharmacology. 1998;56(1):121–129. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(98)00119-1

- Pattaravimonporn N, Chaikijurajai T, Chamroonrat W, Sriphrapradang C. Myxedema Psychosis after Levothyroxine Withdrawal in Radioactive Iodine Treatment of Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: A Case Report. Case Reports in Oncology. 2021;14(3):1596–1600. doi: 10.1159/000520128

- Nagamachi S, Jinnouchi S, Nishii R, et al. Cerebral blood flow abnormalities induced by transient hypothyroidism after thyroidectomy – analysis by tc-99m-HMPAO and SPM96. Annals of Nuclear Medicine. 2004;18(6):469–477. doi: 10.1007/BF02984562

- Constant EL, De Volder AG, Ivanoiu A, et al. Cerebral blood flow and glucose metabolism in hypothyroidism: a positron emission tomography study. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2001;86(8):3864–3870. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.8.7749

- Duntas LH, Biondi B. Short-term hypothyroidism after Levothyroxine-withdrawal in patients with differentiated thyroid cancer: clinical and quality of life consequences. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2007;156(1):13–19. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02310

- Kao PF, Lin JD, Chiu CT, et al. Gastric emptying function changes in patients with thyroid cancer after withdrawal of thyroid hormone therapy. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2004;19(6):655–660. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2003.03326.x

- Botella-Carretero JI, Prados A, Manzano L, et al. The effects of thyroid hormones on circulating markers of cell-mediated immune response, as studied in patients with differentiated thyroid carcinoma before and during thyroxine withdrawal. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2005;153(2):223–230. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.01951

- Duranton F, Lacoste A, Faurous P, et al. Exogenous thyrotropin improves renal function in euthyroid patients, while serum creatinine levels are increased in hypothyroidism. Clinical Kidney Journal. 2013;6(5):478–483. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sft092

- Coura-Filho GB, Willegaignon J, Buchpiguel CA, Sapienza MT. Effects of thyroid hormone withdrawal and recombinant human thyrotropin on glomerular filtration rate during radioiodine therapy for well-differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2015;25(12):1291–1296. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0173

- An YS, Lee J, Kim HK, Lee SJ, Yoon JK. Effect of withdrawal of thyroid hormones versus administration of recombinant human thyroid-stimulating hormone on renal function in thyroid cancer patients. Scientific Reports. 2023;13(1). doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-27455-0

- Den Hollander JG, Wulkan RW, Mantel MJ, Berghout A. Correlation between severity of thyroid dysfunction and renal function. Clinical Endocrinology. 2005;62(4):423–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2005.02236.x

- Cho YY, Kim SK, Jung JH, et al. Long-term outcomes of renal function after radioactive iodine therapy for thyroid cancer according to preparation method: thyroid hormone withdrawal vs. recombinant human thyrotropin. Endocrine. 2019;64(2):293–298. doi: 10.1007/s12020-018-1807-x

- Kreisman SH, Hennessey JV. Consistent Reversible Elevations of Serum Creatinine Levels in Severe Hypothyroidism. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1999;159(1):79–82. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.1.79

- Mariani LH, Berns JS. The Renal Manifestations of Thyroid Disease. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2012;23(1):22–26. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010070766

- Kim SK, Yun GY, Kim KH. et al. Severe hyponatremia following radioactive iodine therapy in patients with differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2014;24(4):773–777. doi: 10.1089/thy.2013.0110

- Nozu T, Yoshida Y, Ohira M, Okumura T. Severe hyponatremia in association with I (131) therapy in a patient with metastatic thyroid cancer. Internal Medicine. 2011;50(19):2169–2174. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.50.5740

- Shakir MK, Krook LS, Schraml FV, Clyde PW. Symptomatic hyponatremia in association with a low-iodine diet and levothyroxine withdrawal prior to I131 in patients with metastatic thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid. 2008;18(7):787–792. doi: 10.1089/thy.2008.0050

- Al Nozha OM, Vautour L, How J. Life-threatening hyponatremia following a low-iodine diet: a case report and review of all reported cases. Endocrine Practice. 2011;17(5):e113–e117. doi: 10.4158/EP11045.CR

- Lee JE, Kim SK, Han KH, et al. Risk factors for developing hyponatremia in thyroid cancer patients undergoing radioactive iodine therapy. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e106840. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106840

- Horie I, Ando T, Imaizumi M, Usa T, Kawakami A. Hyperkalemia develops in some thyroidectomized patients undergoing thyroid hormone withdrawal in preparation for radioactive iodine ablation for thyroid carcinoma. Endocrine Practice. 2015;21(5):488–494. doi: 10.4158/EP14532.OR

- Hyer S, Kong A, Pratt B, Harmer C. Salivary gland toxicity after radioiodine therapy for thyroid cancer. Clinical Oncology. 2007;19(1):83–86. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2006.11.005

- Riachy R, Ghazal N, Haidar MB, Elamine A, Nasrallah MP. Early Sialadenitis After Radioactive Iodine Therapy for Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: Prevalence and Predictors. International Journal of Endocrinology. 2020;2020:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2020/8649794

- Adramerinas M, Andreadis D, Vahtsevanos K, Poulopoulos A, Pazaitou-Panayiotou K. Sialadenitis as a complication of radioiodine therapy in patients with thyroid cancer: where do we stand? Hormones. 2021;20(4):669–678. doi: 10.1007/s42000-021-00304-3

- Silberstein E. Prevention of radiation sialadenitis and glossitis after radioiodine-131 therapy of thyroid cancer. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2007;48 Suppl. 2.

- Ma C, Xie J, Jiang Z, Wang G, Zuo S. Does amifostine have radioprotective effects on salivary glands in high-dose radioactive iodine-treated differentiated thyroid cancer. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 2010;37(9):1778–1785. doi: 10.1007/s00259-009-1368-6

- Nakada K, Ishibashi T, Takei T. Does lemon candy decrease salivary gland damage after radioiodine therapy for thyroid cancer? Journal of nuclear medicine. 2005;46(2):261–266.

- Le Roux MK, Graillon N, Guyot L. Salivary side effects after radioiodine treatment for differentiated papillary thyroid carcinoma: Long-term study. Head & Neck. 2020;42(11):3133–3140. doi: 10.1002/hed.26359

- Jentzen W, Balschuweit D, Schmitz J, et al. The influence of saliva flow stimulation on the absorbed radiation dose to the salivary glands during radioiodine therapy of thyroid cancer using (124) I PET(/CT) imaging. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 2010;37(12):2298–2306. doi: 10.1007/s00259-010-1532-z

- Trukhin AA, Yartsev VD, Sheremeta MS, et al. Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction Secondary to Radioactive Iodine-131 Therapy for Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. The Bulletin of the Scientific Centre for Expert Evaluation of Medicinal Products. Regulatory Research and Medicine Evaluation. 2022;12(4):415–424. doi: 10.30895/1991-2919-2022-12-4-415-424

- Iakovou I, Goulis DG, Tsinaslanidou Z,et al. Effect of recombinant human thyroid-stimulating hormone or levothyroxine withdrawal on salivary gland dysfunction after radioactive iodine administration for thyroid remnant ablation. Head & Neck. 2016;38 Suppl. 1:E227–230. doi: 10.1002/hed.23974

- Rosario PW, Calsolari MR. Salivary and lacrimal gland dysfunction after remnant ablation with radioactive iodine in patients with differentiated thyroid carcinoma prepared with recombinant human thyrotropin. Thyroid. 2013;23(5):617–619. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.0050

- Molenaar RJ, Sidana S, Radivoyevitch T, et al. Risk of Hematologic Malignancies After Radioiodine Treatment of Well-Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2018;36(18):1831–1839. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.0232

- Signore A, Campagna G, Marinaccio J, et al. Analysis of Short-Term and Stable DNA Damage in Patients with Differentiated Thyroid Cancer Treated with 131I in Hypothyroidism or with Recombinant Human Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone for Remnant Ablation. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2022;63(10):1515–1522. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.121.263442

- Sohn SY, Choi JY, Jang HW, et al. Association between excessive urinary iodine excretion and failure of radioactive iodine thyroid ablation in patients with papillary thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2013;23(6):741–747. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.0136

- Lakshmanan M, Schaffer A, Robbins J, Reynolds J, Norton J. A simplified low iodine diet in I-131 scanning and therapy of thyroid cancer. Clinical Nuclear Medicine. 1988;13(12):866–868. doi: 10.1097/00003072-198812000-00003

- Maxon HR, Thomas SR, Boehringer A, et al. Low iodine diet in I-131 ablation of thyroid remnants. Clinical Nuclear Medicine. 1983;8(3):123–126. doi: 10.1097/00003072-198303000-00006

- Tala Jury HP, Castagna MG, Fioravanti C, et al. Lack of association between urinary iodine excretion and successful thyroid ablation in thyroid cancer patients. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2010;95(1):230–237. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1624

- Lee M, Lee YK, Jeon TJ, et al. Low iodine diet for one week is sufficient for adequate preparation of high dose radioactive iodine ablation therapy of differentiated thyroid cancer patients in iodine-rich areas. Thyroid. 2014;24(8):1289–1296. doi: 10.1089/thy.2013.0695

- Tobey AE, Hongxiu L, Auh S, et al. Urine iodine excretion exceeding 250 ug/24h is associated with higher likelihood of progression in intermediate and high-risk thyroid cancer patients treated with radioactive iodine [abstract]. Thyroid. 2018;28 Suppl. 1:A40–A41

- Pluijmen MJ, Eustatia-Rutten C, Goslings BM, et al. Effects of low-iodide diet on postsurgical radioiodide ablation therapy in patients with differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Clinical Endocrinology. 2003;58(4):428–435. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2003.01735.x

- Morris LF, Wilder MS, Waxman AD, Braunstein GD. Reevaluation of the impact of a stringent low-iodine diet on ablation rates in radioiodine treatment of thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid. 2001;11(8):749–755. doi: 10.1089/10507250152484583

- Yoo IDKS, Kim SH, Seo YY, et al. The success rate of initial (131) i ablation in differentiated thyroid cancer: comparison between less strict and very strict low iodine diets. Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 2012;46(1):34–40. doi: 10.1007/s13139-011-0111-y

- Ito S, Iwano S, Kato K, Naganawa S. Predictive factors for the outcomes of initial I-131 low-dose ablation therapy to Japanese patients with differentiated thyroid cancer. journal article. Annals of Nuclear Medicine. 2018;32(6):418–424. doi: 10.1007/s12149-018-1261-0

- Lim CY, Kim JY, Yoon MJ, et al. Effect of a low iodine diet vs. restricted iodine diet on postsurgical preparation for radioiodine ablation therapy in thyroid carcinoma patients. Yonsei Medical Journal. 2015;56(4):1021–1027. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2015.56.4.1021

- Kim HK, Lee SY, Lee JI, et al. Daily urine iodine excretion while consuming a low-iodine diet in preparation for radioactive iodine therapy in a high iodine intake area. Clinical Endocrinology. 2011;75(6):851–856. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2011.04157.x

- Tomoda C, Uruno T, Takamura Y, et al. Reevaluation of stringent low iodine diet in outpatient preparation for radioiodine examination and therapy. Endocrine Journal. 2005;52(2):237–240. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.52.237

- Sohaimi WF, Abdul Manap M, Kasilingam L, et al. Randomised controlled trial of one-week strict low-iodine diet versus one-week non-specified low iodine diet in differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Iranian Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2019;27(2):99–105.

- Dekker BL, Links MH, Muller Kobold AC, et al. Low-Iodine Diet of 4 Days Is Sufficient Preparation for 131I Therapy in Differentiated Thyroid Cancer Patients. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2022;107(2):e604–e611. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgab691

- Padovani RP, Maciel RM, Kasamatsu TS, et al. Assessment of the Effect of Two Distinct Restricted Iodine Diet Durations on Urinary Iodine Levels (Collected over 24 h or as a Single-Spot Urinary Sample) and Na (+)/I (-) Symporter Expression. European Thyroid Journal. 2015;4(2):99–105. doi: 10.1159/000433426

- Park JT, Hennessey JV. Two-week low iodine diet is necessary for adequate outpatient preparation for radioiodine rhTSH scanning in patients taking levothyroxine. Thyroid. 2004;14(1):57–63. doi: 10.1089/105072504322783858

- Dekker BL, Touw DJ, van der Horst-Schrivers ANA, et al. Use of Salivary Iodine Concentrations to Estimate the Iodine Status of Adults in Clinical Practice. The Journal of Nutrition. 2021;151(12):3671–3677. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxab303

补充文件