Computer tomography of uro-lymphatic fistulas associated with renal colic

- Autores: Gelezhe P.B.1,2, Goryacheva K.M.3

-

Afiliações:

- Moscow Center for Diagnostics and Telemedicine

- European Medical Center

- The First Sechenov Moscow State Medical University (Sechenov University)

- Edição: Volume 3, Nº 2 (2022)

- Páginas: 149-155

- Seção: Case reports

- ##submission.dateSubmitted##: 07.04.2022

- ##submission.dateAccepted##: 26.05.2022

- ##submission.datePublished##: 14.07.2022

- URL: https://jdigitaldiagnostics.com/DD/article/view/106050

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.17816/DD106050

- ID: 106050

Citar

Resumo

This article presents two clinical observations of uro-lymphatic fistulas diagnosed by computed tomography. In both cases, the patients were admitted with symptoms of renal colic. Uro-lymphatic fistulas are a rare condition caused by the formation of a connection between the urinary and lymphatic systems, which is caused by, as a rule, lymphatic vessel obstruction due to parasitic infestation. Other causes may be radiation therapy, retroperitoneal trauma, and tumor sprouting. In the era before antibiotics, infectious processes such as xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis and renal tuberculosis were common. Cases of uro-lymphatic fistulas formed against urolithiasis background are presented below. In the clinical cases presented, urine directly entered the lymphatic vessels through a uro-lymphatic fistula detected on contrast-enhanced computed tomography. Uro-lymphatic fistulas caused by impaired urine outflow due to blocked urinary tract are rarely detected since abdominal ultrasound is the diagnostic method of choice in renal colic. In the vast majority of cases, uro-lymphatic fistulas are treated conservatively and do not require surgical intervention. As a rule, the formed fistulas cease to exist when its root cause is successfully treated.

Palavras-chave

Texto integral

BACKGROUND

An abnormal connection between the urinary system and lymphatic vessels is known as urolymphatic fistula (ULF), which is a rare disorder. In most cases, such fistulas are clinically associated with chyluria [1]. ULF is usually caused by parasitic infections of the kidneys or lymphatic system, including filariasis, echinococcosis, cysticercosis, ascariasis, malaria, and renal tuberculosis [2, 3]. The ULF, however, is rarely associated with renal colic. Only isolated cases are reported in world literature [3].

We present two cases of ULF associated with renal colic.

CLINICAL CASES

Clinical case No. 1

At approximately 3 am, a 65-yr-old male patient woke up with a dull, aching pain in his left iliac region [visual analogue scale (VAS) score: 3–4]. The pain intensity remained the constant both at rest and on movement. The antispasmodic the patient took had no effect. To relieve the condition, he came to the clinic.

Clinical examination revealed a stable and closer to satisfactory condition. There were no respiratory or hemodynamic disorders. The respiration rate was 18/min. The pulse was 74/min. The abdomen was unswollen, soft, and sensitive in the left iliac region. There were no peritoneal signs were observed. Auscultation of bowel sounds was done. Flatus was passing. There is no dysuria. The right costovertebral angle tenderness was positive. There were no abnormalities in urinalysis. Blood tests revealed leukocytosis with left shift.

The left renal colic was suggested in the emergency room. The patient was referred for an intravenous contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and kidneys to confirm that diagnosis and exclude a sigmoid diverticulitis.

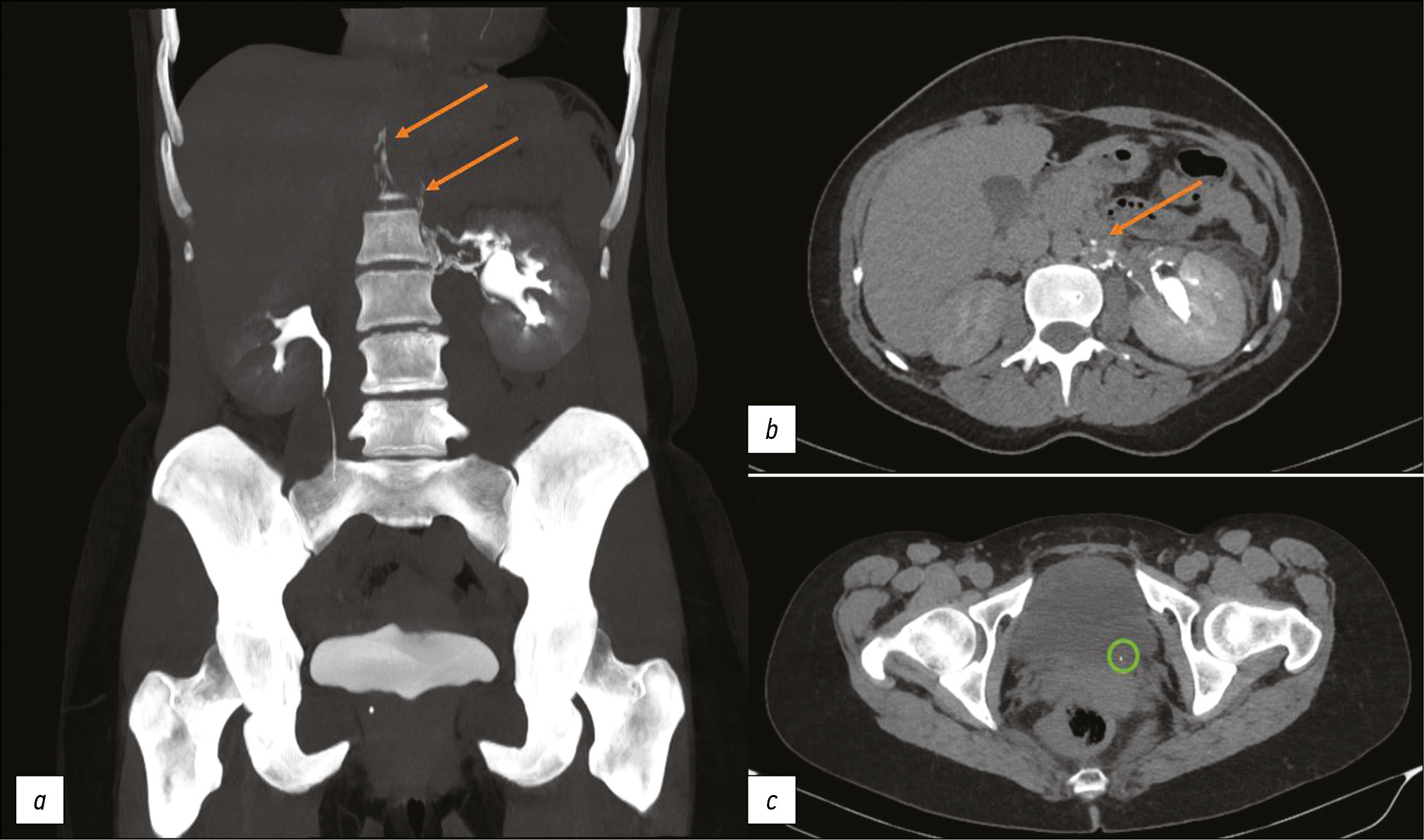

At 15 min, the CT revealed a small peripelvic contrast extravasation (urinoma) (during the delayed phase). In addition, the retrograde contrast enhancement of lymphatic vessels was observed along the left renal vein during the excretory phase. These signs are typical for ULF. The examination showed the calculus at the left ureteric orifice, left ureteropyelocalicoectasia, left peripelvic urinoma, and right renal calculus (Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Computed tomography of the abdomen with intravenous contrast enhancement. The excretory phase: (a, b) Orange arrows show the contrast spreading along lymphatic vessels; (c) A green circle highlights a calculus at the left ureteric orifice.

The left ureteric calculus had urodynamic effects on the left upper urinary tract resulting in high risk of purulent-septic complications, so the left contact lithotripsy was initiated.

Surgery Report Summary. Ureteroscope No. 7 was freely passed through the urethra into the bladder. The ureteric orifices were slit-shaped and typically located. A large black calculus protruded from the left ureteric orifice into the bladder. For safety, a core wire was guided to the left ureteric orifice. The calculus was also moved into the ureter. The ureteroscope was inserted into the left ureter. Laser lithotripsy was performed. Calculus fragments were removed. Over the previously inserted wire, stenting catheter No. 6 was guided from the left side, having the proximal end folded in the pelvis and the distal one in the bladder.

The patient was discharged the next day for further outpatient treatment and follow-up.

Clinical case No. 2

The previous, a 38-yr-old female patient complained gradually increasing lumbar pain (VAS score: up to 3). Clinical examination revealed that the general condition was relatively satisfactory. The abdomen was soft and painless. There were no peritoneal signs observed. The right costovertebral angle tenderness was positive. Complete blood count was normal. The left renal colic was suspected in the emergency room. To confirm the diagnosis, a contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen and pelvis was recommended.

The CT showed a contrast extravasation in the left kidney lymphatic ductus up to the thoracic lymphatic duct (typical for ULF). A calculus at the left ureteric orifice with ureteropyelocalicectasis and signs of urinary tract obstruction, as well as a calculus at left middle calix, were found during the examination (Figure 2).

Fig. 2. Computed tomography of the abdomen with intravenous contrast enhancement. The excretory phase: (a, b) Orange arrows show the contrast spread along lymphatic vessels; (c) A green circle highlights a calculus at the left ureteric orifice.

The patient refused hospitalization and was referred to a third-party hospital for further treatment.

DISCUSSION

Fistulas of the urinary system can communicate with the intestines, skin, blood and lymphatic vessels, and thoracic cavity (pleura, bronchi) [3]. Urinary fistulas can be divided into two: those that communicate with renal collecting tubules via the renal parenchyma and those that communicate directly with the renal pelvis. The relatively abundant lymphatic vessels of the renal pelvis eventually communicates with the retroperitoneal lymphatic system via the peripelvic system [4, 5].

In developed countries, most cases of fistulas involving the kidney are caused by iatrogenic trauma, such as percutaneous nephrostomy or nephrolithotomy guidewire insertion, extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, and abdominal surgery. Other causes include radiation therapy, penetrating trauma, and neoplastic invasion. Chronic infections commonly associated with calculi formation (xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis) and tuberculosis have become less common causes due to development of next generation antibiotics [3].

In our clinical cases, urine directly entered the lymphatic vessels through the ULF detected by contrast-enhanced CT. Following the obstruction of the urinary system, the ULF developed (Figure 3). The reported cases are relatively unique because most ULFs are caused by obstruction of lymphatic vessels. The ULF is often followed by chyluria caused by lymphatic fluid penetration into the urinary system [1]. In our cases, no chyluria was detected, possibly as a result of the directed urine flow from the urinary system to lymphatic vessels in the setting of increased pressure in the urinary system [6].

Fig. 3. A schematic shows the mechanism of urolymphatic fistula formation associated with impaired urine outflow due to the ureteral calculus (yellow arrow).

Since most cases of renal colic are diagnosed using abdominal radiography and ultrasound, urolithiasis-related ULFs are rarely detected [3, 7]. The excretory phase CT is advised if the urinary and lymphatic systems are still connected after the ureteral obstruction. In other causes of the lymphatic system occlusion, it is possible to perform lymphography[8].

In most cases, ULFs are treated conservatively [8, 9]. Fistulas usually close after the treatment of the underlying condition.

The reported cases have some limitations. The fistulas described could theoretically exist before the current attack of renal colic. The first patient did not have a CT scan of the urinary system after the treatment, so we do not know whether the fistula persisted after lithotripsy and ureteral stenting.

CONCLUSION

As a result, these ULFs were detected as a part of examination due to renal colic attacks and were confirmed by contrast-enhanced CT. Despite the direct urine penetration into lymphatic vessels, no significant clinical changes were observed.

Further research is required to determine clinical consequences of this disorder.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Funding source. This study was not supported by any external sources of funding.

Competing interests. The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contribution. All authors made a substantial contribution to the conception of the work, acquisition, analysis, interpretation of data for the work, drafting and revising the work, final approval of the version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. P.B. Gelezhe ― selection and analysis of literary data, writing the text of the article, illustrations creating; K.M. Goryacheva ― illustrations creating.

Sobre autores

Pavel Gelezhe

Moscow Center for Diagnostics and Telemedicine; European Medical Center

Autor responsável pela correspondência

Email: gelezhe.pavel@gmail.com

ORCID ID: 0000-0003-1072-2202

Código SPIN: 4841-3234

MD, Cand. Sci. (Med.)

Rússia, Moscow; MoscowKristina Goryacheva

The First Sechenov Moscow State Medical University (Sechenov University)

Email: cristina.imago27@yandex.ru

ORCID ID: 0000-0003-1221-9694

Código SPIN: 2722-6891

Rússia, Moscow

Bibliografia

- Stainer V, Jones P, Juliebo SO, et al. Chyluria: what does the clinician need to know? Ther Adv Urol. 2020;(12):1756287220940899. doi: 10.1177/1756287220940899

- Roffi F, Eiss D, Petit F, et al. Pyelolymphatic fistula in a patient with lymphatic filariasis: a case report. (In French). J Radiol. 2007;88(12):1896–1898. doi: 10.1016/s0221-0363(07)78369-5

- Yu NC, Raman SS, Patel M, et al. Fistulas of the genitourinary tract: a radiologic review. Radiographics. 2004;24(5):1331–1352. doi: 10.1148/rg.245035219

- McIntosh GH, Morris B. The lymphatics of the kidney and the formation of renal lymph. J Physiology. 1971;214(3):365–376. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1971.sp009438

- Skandalakis JE, Skandalakis LJ, Skandalakis PN. Anatomy of the Lymphatics. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2007;16(1):1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2006.10.006

- Diamond E, Schapira HE. Chyluria ― a review of the literature. Urology. 1985;26(5):427–431. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(85)90147-5

- Rajaonarison N, Ahmad A, Cucchi JM, et al. Reversible uro-lymphatic fistula. Clin Imaging. 2012;36(1):72–74. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2011.04.012

- Graziani G, Cucchiari D, Verdesca S, et al. Chyluria associated with nephrotic-range proteinuria: pathophysiology, clinical picture and therapeutic options. Nephron Clinical Practice. 2011;119(3):248–253. doi: 10.1159/000329154

- Kim RJ, Joudi FN. Chyluria after partial nephrectomy: case report and review of the literature. Sci World J. 2009;(9):1–4. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2009.5

Arquivos suplementares